The Wonders of Birding in Portugal

Story and Photos by Tim Gallagher

From the Summer 2015 issue of Living Bird magazine.

July 15, 2015

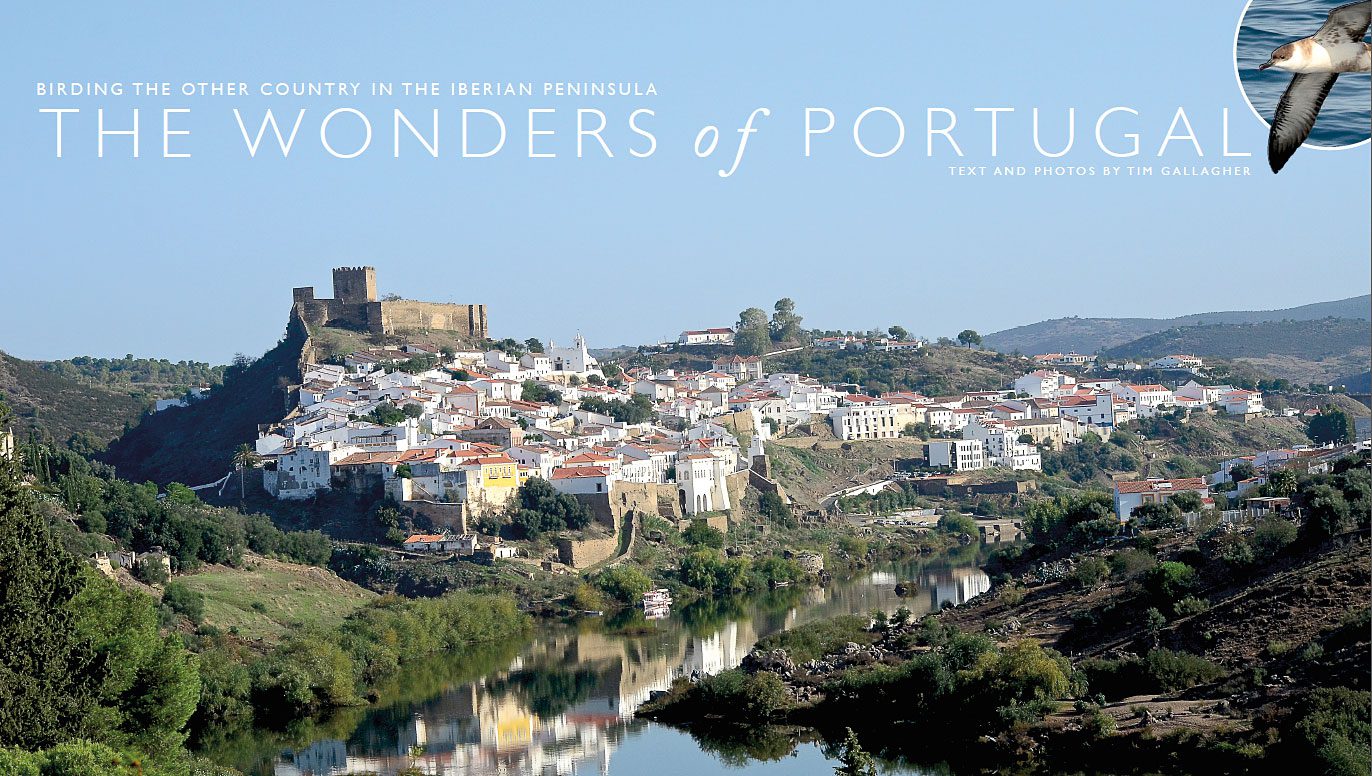

So, how much do you know about Portugal? For me, most of what I know dates back to what I learned in junior high school—the great explorers who set sail from its shores some 500 years ago: Vasco de Gama, the first European to reach India by sea; Ferdinand Magellan, the first to circumnavigate the Earth—although he died before his five ships made it back to Portugal. (As a quick bird note, the Magellanic Penguin was named after Magellan, because he and his crew were the first Europeans to see it.)

One thing you can accurately say about Portugal is that as a birding destination it has been greatly neglected. Just ask any Portuguese birder or nature tour guide and they’ll tell you: the vast majority of birding tourists opt to visit the country’s next-door neighbor, Spain. The two countries share the Iberian Peninsula, at the southwestern edge of Europe, and have most of the same birds, but Portugal is significantly smaller. (Spain is 194,896 square miles, compared with 35,603 square miles for Portugal.) You can drive for hours in Spain to get from one birding hotspot to another, whereas in Portugal, there are some great places to bird less than an hour’s drive from Lisbon.

One of Portugal’s top birders and tour guides, João Jara, offered to pick me up at Lisbon Airport and spend a week traveling with Matt Merritt (editor of the popular British magazine, Bird Watching) and me through southwestern Portugal, sampling its abundant birdlife. Although I’d never met João before and he was not holding a sign with my name on it at the airport’s exit gate, we somehow recognized each other instantly. Maybe it was the intensity of his dark eyes as he scanned the crowd—like a Peregrine Falcon peering at a flock of pigeons—or the way we were both dressed, like we were ready to step instantly into a field or marsh. Or perhaps it was the binoculars we both had strapped around our necks.

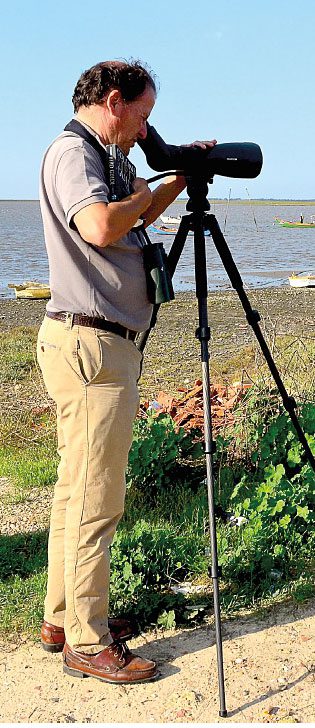

Matt arrived soon after, and we were on our way. What amazed me most was how quickly we were in the field birding. Less than 20 minutes after loading our luggage into the back of his car at Lisbon Airport, we arrived at the edge of a tidal mudflat in the Tagus Estuary, one of the most important wetlands in Europe. João stood like a statue at his spotting scope—scanning shorebird flocks with all the intensity of a microbiologist peering through a microscope at swarms of bacteria, trying to spot one that looks slightly different. His single-mindedness as a birder has definitely paid off for him. Over the years he has turned up an amazing array of rarities, including Portugal’s first Surf Scoter, first nesting pair of Glossy Ibis, and numerous second, third, and fourth sightings for the country.

On this day, João quickly pointed out a Marsh Sandpiper—an Eastern European species that is usually seen only two or three times a year in Portugal. A short time later, we headed to a nearby semi-open area with numerous cork trees and enjoyed close-up views of a Black-shouldered Kite. We then moved farther up the estuary, which abounded with Greater Flamingos, foraging in the shallow water and flying past overhead. We also encountered a Bonelli’s Eagle, which made a spectacular diving attack on a Northern Lapwing and barely missed capturing it. When I was a teenager, I’d seen a falconer in California hunt jackrabbits with a captive Bonnelli’s Eagle, and it was an impressive bird—smaller than a Golden Eagle but still a swift and agile hunter. But this was a life bird for me in the wild. I would see many more of them in the days ahead.

The next morning we entered the steppe country near Castro Verde, a land of parched, rocky hills, covered with dry grass, which reminded me of parts of Central California. On this day, often driving on dirt roads through agricultural areas, we searched for Great Bustard and Black-bellied Sandgrouse. We checked several places and finally heard a sandgrouse calling. An instant later, a flock of 17 flew past us and landed nearby. (We didn’t find any Great Bustards until the following morning.)

Then João drove us to a place across from a vineyard, a high hill with rocky outcroppings on top—the known territory of a Spanish Imperial Eagle pair. We waited for half an hour in the blazing sun without a sighting, all the while João assuring us that something would happen soon—until a pair of the eagles came soaring in at the top of the hill. We heard the female’s call, sounding almost raven-like, followed soon after by the male’s, which reminded me of the bark of a small dog. We gazed upward at the soaring male for a long time, and also had a flyover by a Bonelli’s Eagle. It was all good—but it soon got better.

As we were driving through the hills to another area, a juvenile Golden Eagle emerged on our right from the valley below, barely above eye level at first as it circled upward on a thermal. We parked and stood outside the car with our binoculars trained on her as she soared higher and higher in the warming afternoon air. Suddenly a Spanish Imperial Eagle came diving down with a great swoosh to drive off the intruder. After a couple of skirmishes high in the sky, an enormous Cinereous Vulture appeared nearby, which was more than the Imperial could stand. Breaking away from the Golden Eagle, it plummeted downward, making a blistering dive across the sky at the huge vulture, which was almost as large as an Andean Condor. And then three Eurasian Griffon Vultures materialized in the open blue sky. We were ecstatic as we followed the action unfolding above us—an angry eagle with a bunch of big raptors to chase.

A couple of days later, we headed to Sagres, the southwesternmost tip of Europe. Sagres is a narrow peninsula where southbound migrating raptors congregate before attempting to fly across the sea to Africa. But there’s too much water for them to cross from Europe to Africa at this point—some 250 miles of open sea—and the birds have to circle back and head southeastward to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the water crossing is only nine miles wide. So you get great concentrations of soaring birds.

On Sagres, we drove out a long dirt road to a semi-open area with a scattering of small conifers. As the morning warmed, the skies filled with soaring raptors—Booted Eagle, Cinereous Vulture, Egyptian Vulture, Bonelli’s Eagle, Black Kite, Eurasian Sparrowhawk, Common Buzzard, European Honey Buzzard. We stood with a dozen or more other birders, intently scanning the sky above us with binoculars and scopes.

Of course, it wasn’t long before João came up with another rarity: a Pallid Harrier—a species of Eastern Europe and Central Asia that virtually never shows up this far west. Photos of the bird have been submitted to the country’s rarities committee, and if the sighting is accepted, it will be only the fourth or fifth record of the species in Portugal. Score another big tick for João!

We decided to spend the last afternoon of our Portugal adventure going on a half-day pelagic birding trip from nearby Sagres Harbor. We sailed aboard a large inflated craft—basically a huge Zodiac with a row of forward-facing saddles on each side. And it was amazing, at times like a wild bronco ride as we bucked the waves going to and from the continental shelf, about 10 miles out. But it was worth it. We saw a scattering of Northern Gannets flying past soon after leaving the harbor. Farther out we were getting close-up flybys by Wilson’s Storm-Petrels as well as Cory’s, Balearic, and Great shearwaters. Matt and I fired away happily with our cameras, nailing numerous full-frame pictures. As a bonus, we also saw (and took pictures of ) many marine mammals, such as harbor porpoises, bottlenosed dolphins, and even a minke whale.

At the end of our journey, we were amazed by how many birds we’d seen—and all within a 90-minute drive from Lisbon Airport.

For more information about planning a trip to Portugal, visit birds.pt or visitportugalbirdwatching.com.

BIRDING SEASONS IN PORTUGAL

BIRDING SEASONS IN PORTUGAL

Winter days in Portugal are balmy and filled with opportunities to see all the great birds that have fled from the frigid climes of northern Europe. In the wetlands of southern Portugal, winter is the peak time to see many aquatic birds, such as flamingos, spoonbills, ibises, waders, herons, egrets, cormorants, ducks, geese, coots, and gulls. Spring is even better, as the many migrants— such as White Storks (above), Black-winged Stilts, Eurasian Hoopoes, Lesser Kestrels, Great Spotted Cuckoos, Black Kites, Short-toed Eagles, Booted Eagles, Montagu’s Harriers, Black Storks, and more—flood back into the country from parts south. But I have no complaints about the time I spent birding there last year in late September and early October. It was wonderful.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library

PORTUGAL FOR NON-BIRDERS

PORTUGAL FOR NON-BIRDERS