Snowbird Season: An Irruption of Boreal Songbirds

By Marie Read January 15, 2009

Here in the Northeast, it is tempting to view winter as the season of loss. Days shorten. The air chills. The bright songbirds of summer depart for warmer climes. Leaves drop from the trees, robbing the landscape of color. All around us, nature seems to be hiding, hunkering down to survive.

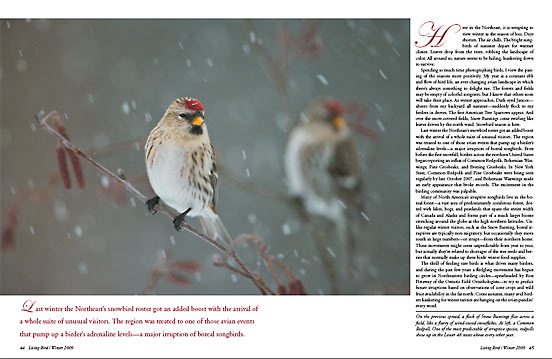

Spending so much time photographing birds, I view the passing of the seasons more positively. My year is a constant ebb and flow of bird life, an ever-changing avian landscape in which there’s always something to delight me. The forests and fields may be empty of colorful songsters, but I know that others soon will take their place. As winter approaches, Dark-eyed Juncos—absent from my backyard all summer—suddenly flock to my feeders in droves. The first American Tree Sparrows appear. And over the snow-covered fields, Snow Buntings come swirling like leaves driven by the north wind. Snowbird season is here.

Last winter the Northeast’s snowbird roster got an added boost with the arrival of a whole suite of unusual visitors. The region was treated to one of those avian events that pump up a birder’s adrenaline levels—a major irruption of boreal songbirds. Even before the first snowfall, birders across the northern United States began reporting an influx of Common Redpolls, Bohemian Waxwings, Pine Grosbeaks, and Evening Grosbeaks. In New York State, Common Redpolls and Pine Grosbeaks were being seen regularly by late October 2007, and Bohemian Waxwings made an early appearance that broke records. The excitement in the birding community was palpable.

Many of North America’s irruptive songbirds live in the boreal forest—a vast area of predominantly coniferous forest, dotted with lakes, bogs, and peatlands that spans the entire width of Canada and Alaska and forms part of a much larger biome stretching around the globe at the high northern latitudes. Unlike regular winter visitors, such as the Snow Bunting, boreal irruptives are typically non-migratory, but occasionally they move south in large numbers—or irrupt—from their northern home. These movements might seem unpredictable from year to year, but actually they’re related to shortages of the tree seeds and berries that normally make up these birds’ winter food supplies.

The thrill of finding rare birds is what drives many birders, and during the past few years a fledgling movement has begun to grow in Northeastern birding circles—spearheaded by Ron Pittaway of the Ontario Field Ornithologists—to try to predict future irruptions based on observations of cone crops and wild fruit availability in the far north. Come autumn, many avid birders hankering for winter rarities are hanging on the avian pundits’ every word.

Probably the easiest to predict is the Common Redpoll, which moves south on average every other year, a pattern that makes it more reliable than other irruptive winter finches. In their northern home, redpolls’ preferred winter diet is primarily birch seeds and other small tree seeds. If the birch crop fails up north, these tiny birds irrupt into the United States, their flocks plying weedy fields and stands of alder and aspen in search of seeds and catkins, or entertaining us at our backyard bird feeders. I never tire of watching a flock of redpolls raining down on my feeders like leaves tumbling from the trees, only to suddenly swirl away in a chittering flock, returning minutes later to do the whole thing again. In New York, last year’s Common Redpoll irruption was particularly memorable, with the species lingering until late March in some areas.

At the opposite end of the predictability spectrum is the Pine Grosbeak, a species that visits the Northeastern United States so infrequently that its arrival always sends birders into a flutter. Its appearance as far south as Connecticut and Massachusetts last winter was a hot topic even in nonbirding circles. Many people got to see these spectacular large finches for the first time—admiring the stunning rose-pink males or the more muted females with their plumage accented in yellowish hues from olive-yellow to intense gold.

Pine Grosbeaks feed on the buds, seeds, and fruits of a wide variety of trees and shrubs, both coniferous and deciduous, and are particularly fond of mountain-ash berries in their normal winter range. When they find themselves in parks and suburban areas during irruption years, they often gravitate to ornamental crabapple trees, clinging upside down on hanging branches to reach the fruit and biting out chunks with their stout bills to extract the nutritious seeds. Pine Grosbeaks preoccupied with feeding can be approachable, a characteristic that lets you really appreciate their richly patterned feathering.

Sound is often the clue that there is an unusual bird mixed in with the usual suspects. An unfamiliar wheezy, upslurred call, somehow different from the calls of an American Goldfinch, has me reaching for my binoculars—somewhere in that goldfinch flock is a Pine Siskin! During irruptions, Pine Siskins wander widely. Winter 2007 found them more widespread over the eastern United States than they had been for several years. These are birds of subtle beauty—brown-streaked finches with just a hint of yellow in their wings and tails—but they’re welcome winter visitors nonetheless. Siskins are conifer-seed specialists, and when not feeding from backyard feeders, they frequent stands of pines, spruces, or firs, extracting seeds from cones with their slender, sharply pointed bills.

One bird sound for me never fails to evoke the frigid, breathtaking, twig-snapping, snow-crunching cold of early morning in the depths of winter—the shrill, icy voice of an Evening Grosbeak. Sadly, it’s a sound that is becoming ever more rare in the Northeast. Gone are the days when these handsome winter visitors thronged backyards, gobbling up sunflower seeds to the extent that birders began grumbling about the cost of stocking their birdfeeders! In fact, the Evening Grosbeak is second only to the Northern Bobwhite on the National Audubon Society’s list of the top 20 common birds in decline, due to its 78 percent population decrease during the past 40 years. The grosbeak feeds mostly on conifer and hardwood seeds in winter, but it feeds its young insects, so the species benefited greatly from spruce-budworm outbreaks in the 1970s and ’80s, the same period during which those huge grosbeak flocks remembered by older birders occurred. Spruce-budworm infestations have been on the decline ever since. Promising numbers of Evening Grosbeaks moved into the Northeast last winter, although we may never again experience those large flocks of yesteryear.

Even during years when no boreal irruption is expected, there’s one snowbird that I look forward to seeing as a true sign that winter has arrived—the Snow Bunting. When snow blankets the land, the twittering flocks come swirling over the weedy, fallow fields in their relentless search for food. The massed buntings seem to roll along like an ocean wave as those at the rear fly forward and land ahead of the frontrunners. Suddenly they take to the air all at once, their voices melding together to sound like the hiss of wave-tumbled pebbles rolling up and down a beach. Then—like a flurry of wind-tossed snowflakes against the leaden sky—they are gone.

For everything there is a season . . . and winter is snowbird season. Enjoy!

Marie Read is a freelance writer and photographer based in Freeville, New York. Her work frequently appears in this magazine. Visit her web site at www.marieread.com.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library