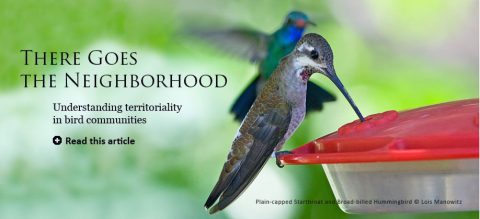

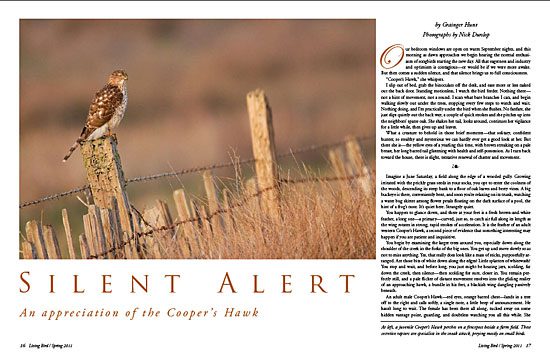

Silent Alert: The Cooper’s Hawk’s Reputation Precedes It

By Grainger Hunt; Photographs by Nick Dunlop

July 15, 2011

Our bedroom windows are open on warm September nights, and this morning as dawn approaches we begin hearing the normal enthusiasm of songbirds starting the new day. All that eagerness and industry and optimism is contagious—or would be if we were more awake. But then comes a sudden silence, and that silence brings us to full consciousness.

“Cooper’s Hawk,” she whispers.

I slip out of bed, grab the binoculars off the desk, and ease more or less naked out the back door. Standing motionless, I watch the bird feeder. Nothing there—not a hint of movement, not a sound. I scan what bare branches I can, and begin walking slowly out under the trees, stopping every few steps to watch and wait. Nothing doing, and I’m practically under the bird when she flushes. No fanfare, she just slips quietly out the back way, a couple of quick strokes and she pitches up into the neighbors’ sparse oak. She shakes her tail, looks around, continues her vigilance for a little while, then gives up and leaves.

What a creature to behold in those brief moments—that solitary, confident hunter, so stealthy and mysterious we can hardly ever get a good look at her. But there she is—the yellow eyes of a yearling this time, with brown streaking on a pale breast, her long barred tail glistening with health and self-possession. As I turn back toward the house, there is slight, tentative renewal of chatter and movement.

Imagine a June Saturday, a field along the edge of a wooded gully. Growing irritated with the prickly grass seeds in your socks, you opt to enter the coolness of the woods, descending its steep bank to a floor of oak leaves and berry vines. A big buckeye is there, conveniently bent, and soon you’re relaxing on its trunk, watching a water bug skitter among flower petals floating on the dark surface of a pool, the hint of a frog’s nose. It’s quiet here. Strangely quiet.

You happen to glance down, and there at your feet is a fresh brown-and-white feather, a long one—a primary—curved, just so, to catch air full along its length as the wing rotates in strong, rapid strokes of acceleration. It is the feather of an adult western Cooper’s Hawk, a second piece of evidence that something interesting may happen if you are patient and inquisitive.

You begin by examining the larger trees around you, especially down along the shoulder of the creek in the forks of the big ones. You get up and move slowly so as not to miss anything. Yes, that really does look like a mass of sticks, purposefully arranged. Are those bits of white down along the edges? Little splatters of whitewash? You stop and wait, and before long, you just might be hearing jays, scolding, far down the creek, then silence—then scolding for sure, closer in. You remain perfectly still, and a pale flicker of distant movement resolves into the gliding reality of an approaching hawk, a bundle in his feet, a blackish wing dangling passively beneath.

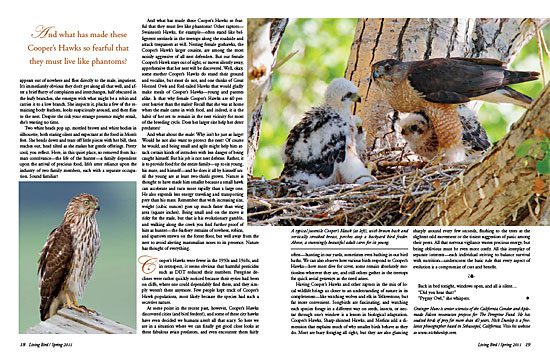

An adult male Cooper’s Hawk—red eyes, orange barred chest—lands in a tree off to the right and calls softly, a single note, a little beep of announcement. He hasn’t long to wait. The female has been there all along, tucked away on some hidden vantage point, guarding, and doubtless watching you all this while. She appears out of nowhere and flies directly to the male, impatient. It’s immediately obvious they don’t get along all that well, and after a brief flurry of complaints and interchanges, half obscured in the leafy branches, she emerges with what might be a robin and carries it to a low branch. She inspects it, plucks a few of the remaining body feathers, looks suspiciously around, and then flies to the nest. Despite the risk your strange presence might entail, she’s wasting no time.

Two white heads pop up, mottled brown and white bodies in silhouette, both staring silent and expectant at the food in Mom’s feet. She bends down and tears off little pieces with her bill, then reaches out, head tilted as she makes her gentle offerings. Pretty cool, you reflect. Here, in this quiet place, so removed from human contrivance—the life of the hunter—a family dependent upon the arrival of precious food, life’s utter reliance upon the industry of two family members, each with a separate occupation. Sound familiar?

And what has made these Cooper’s Hawks so fearful that they must live like phantoms? Other raptors—Swainson’s Hawks, for example—often stand like belligerent sentinels in the treetops along the roadside and attack trespassers at will. Nesting female goshawks, the Cooper’s Hawk’s larger cousins, are among the most noisily aggressive of all nest defenders. But our female Cooper’s Hawk stays out of sight, or moves silently away, apprehensive that her nest will be discovered. Well, okay, some mother Cooper’s Hawks do stand their ground and vocalize, but most do not, and one thinks of Great Horned Owls and Red-tailed Hawks that would gladly make meals of Cooper’s Hawks—young and parents alike. Is that why female Cooper’s Hawks are 40 percent heavier than the males? Recall that she was at home when the male came in with food, and indeed, it is the habit of her sex to remain in the nest vicinity for most of the breeding cycle. Does her larger size help her deter predators?

And what about the male: Why isn’t he just as large? Would he not also want to protect the nest? Of course he would, and being small and agile might help him attack certain kinds of intruders with less danger of being caught himself. But his job is not nest defense. Rather, it is to provide food for the entire family—up to six young, his mate, and himself—and he does it all by himself until the young are at least two-thirds grown. Nature is thought to have made him smaller because a small hawk can accelerate and turn more rapidly than a large one. He also expends less energy traveling and transporting prey than his mate. Remember that with increasing size, weight (cubic ounces) goes up much faster than wing area (square inches). Being small and on the move is risky for the male, but that is his evolutionary gamble, and walking along the creek you find further proof of him as hunter—the feathery remains of towhees, robins, and sparrows strewn on the forest floor, but well away from the nest to avoid alerting mammalian noses to its presence. Nature has thought of everything.

Cooper’s Hawks were fewer in the 1950s and 1960s, and in retrospect, it seems obvious that harmful pesticides such as DDT reduced their numbers. Peregrine declines were rather quickly noticed because their eyries had been on cliffs, where one could dependably find them, and they simply weren’t there anymore. Few people kept track of Cooper’s Hawk populations, most likely because the species had such a secretive nature.

At some point in the recent past, however, Cooper’s Hawks discovered cities (and bird feeders!), and some of these city hawks have even decided we humans aren’t all that scary. So here we are in a situation where we can finally get good close looks at these fabulous avian predators, and even encounter them fairly often—hunting in our yards, sometimes even bathing in our bird baths. We can also observe how various birds respond to Cooper’s Hawks—how most dive for cover, some remain absolutely motionless wherever they are, and still others gather in the treetops for quick aerial getaways as the need arises.

Having Cooper’s Hawks and other raptors in the mix of local wildlife brings us closer to an understanding of nature in its completeness—like watching wolves and elk in Yellowstone, but far more convenient. Songbirds are fascinating, and watching each species forage in a different way on seeds, insects, or nectar through one’s window is a lesson in biological adaptation. Cooper’s Hawks, Sharp-shinned Hawks, and Merlins add a dimension that explains much of why smaller birds behave as they do. Most are busy foraging all right, but they are also glancing sharply around every few seconds, flushing to the trees at the slightest odd movement or the tiniest suggestion of panic among their peers. All that nervous vigilance wastes precious energy, but being oblivious must be even more costly. All this interplay of separate interests—each individual striving to balance survival with nutrition—underscores the basic rule that every aspect of evolution is a compromise of cost and benefit.

Back in bed tonight, windows open, and all is silent…

“Did you hear that?”

“Pygmy Owl,” she whispers.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library