Birds of Light and Shadow: Intricate Illusions in Paper

By Pat Leonard

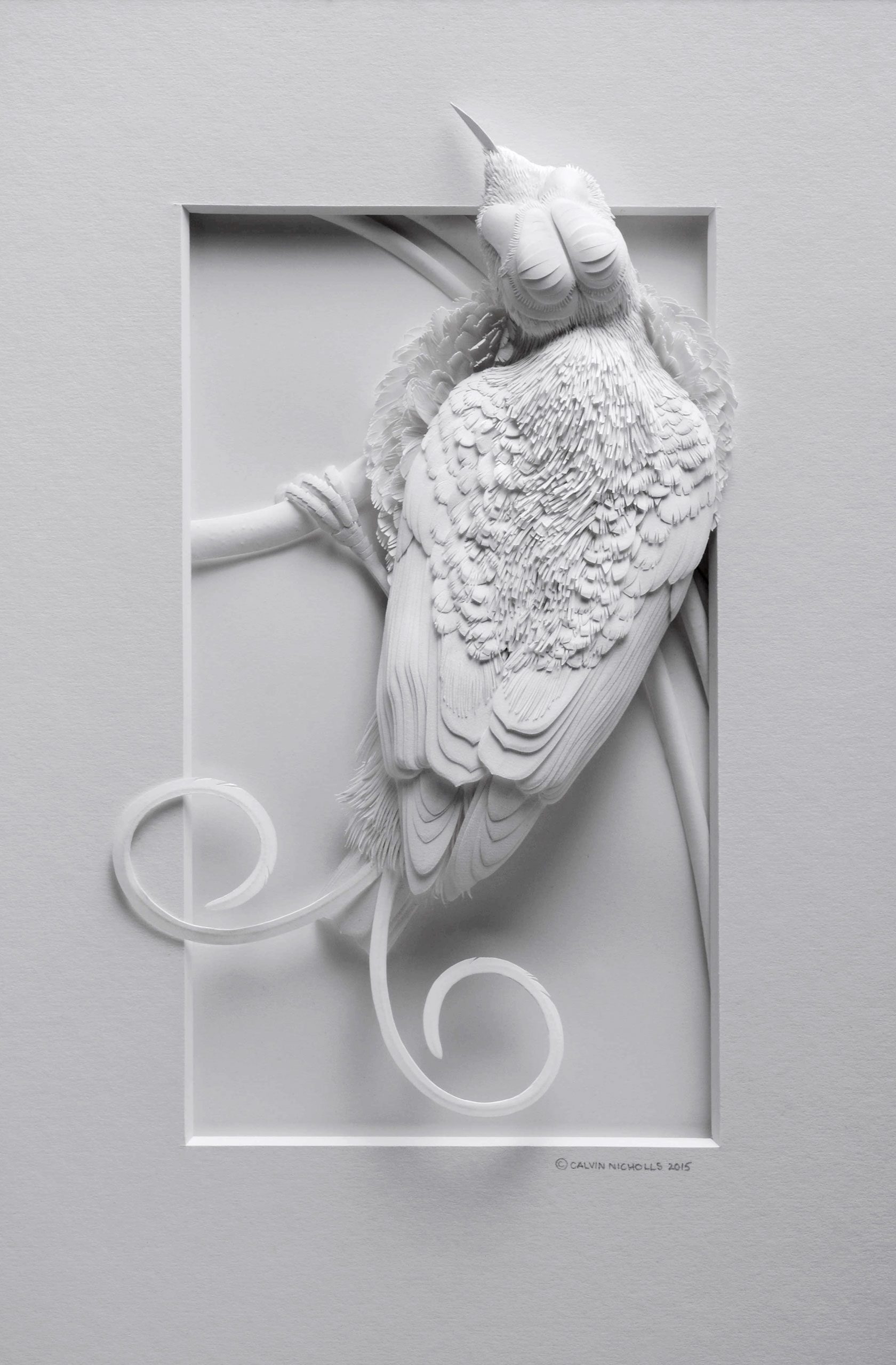

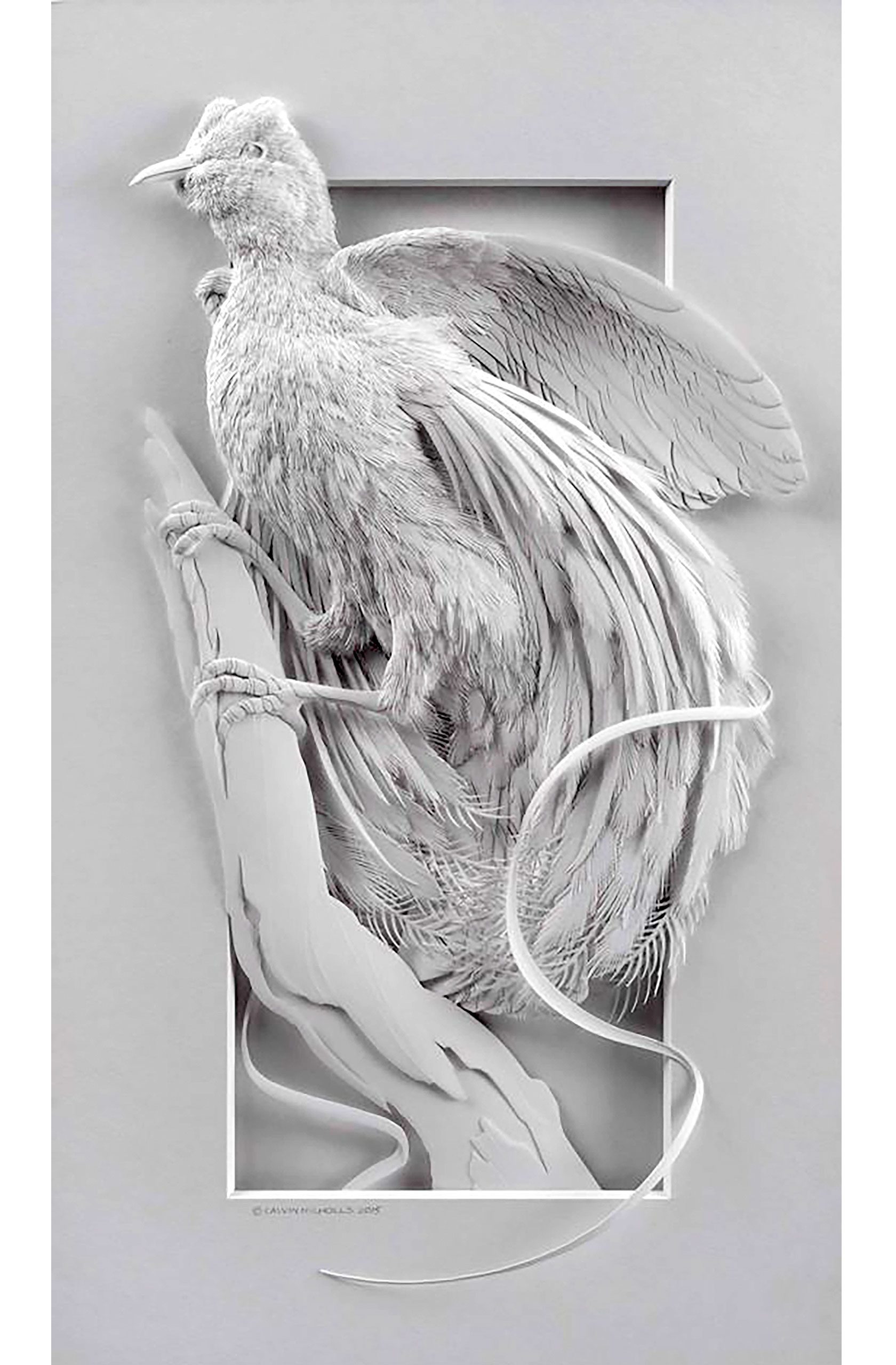

Greater Bird-of-Paradise by Calvin Nicholls. December 19, 2018From the Winter 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The daily commute to his attic studio is short and steep. The road to success for Canadian artist Calvin Nicholls has been much longer. He’s spent the last 30 years perfecting an unusual art form that is all about light, shadow, shape—and illusion. Nicholls is a paper sculptor who creates fantastically detailed birds and other animals that seem to leap, lean, or flutter straight out of their frames. His career evolved from drawing, model-making, sculpting, photography, and periodic doses of serendipity.

“It’s so clear in my mind—it was 1983,” says Nicholls. “I had my own graphic design studio in Toronto. I met a fellow who was manipulating paper to produce areas of highlight and shadow to create the feeling of depth in two dimensions. We worked on a restaurant menu concept together and I could see the potential in this technique. I got playing with paper sculpture myself and it was just so much fun.”

At first, Nicholls created his sculptures as a method for creating his final product, a photograph that could surprise viewers by seeming three dimensional. The technique turned out to be a hit when Nicholls introduced it to some of his clients. He showed photographic prints of his work in an art show in Ontario in 1990, but he also wound up selling sculptures of a Snowy Owl and Mallard as well.

“I was focused on the prints and trying to make two dimensions look like three,” Nicholls says. “Then clients would say, so where’s the artwork? And I thought, yikes—I never even thought about displaying the artwork! I still marvel that I didn’t know then that the original artwork could be as interesting as the illusion created in the prints with sophisticated studio lighting.”

Switching focus to the original artwork meant reducing the depth of his sculptures so they could be framed and so the jumble of foam core supports and toothpicks underneath didn’t show when the piece was viewed from an angle. It took a lot of time and experimentation. But the end result is an uncanny illusion of depth from layers of paper that are only about an inch thick.

A series of 75 commissioned sculptures for Follett Library Resources near Chicago provided steady income during the years he and his wife Anne raised their three children. Completed over 16 years, the collection is breathtaking. Eagles pounce. A lynx leaps. A hedgehog huddles and ducklings dabble.

“One strong characteristic of my work is realistic detail,” Nicholls explains. “I feel really, really motivated to get as much detail as I can in fur and feathers to set my work apart. Birds are perfect subjects because of the layering of their feathers. I’m most often asked to do birds or some aspect of nature. I feel like some of the best examples of what I do are birds, though my most recent work sparked a new enthusiasm for working in a much larger format on both birds and mammals.”

Fate stepped in again when a client and art collector came across Birds of Paradise: Revealing the World’s Most Extraordinary Birds, a 2012 book by Cornell Lab scientist Ed Scholes and wildlife photojournalist Tim Laman. The book features spectacular photos of all 39 bird-of-paradise species known at the time (number 40 was described in 2018). Scholes and Laman studied, photographed, and videotaped them all during more than a decade of rugged expeditions to New Guinea.

The client asked Nicholls to create one large bird-of-paradise piece and four smaller ones. The artist turned to Scholes and Laman for their expertise, wanting to get the birds exactly right. Not only are these stunningly beautiful birds, many of them morph into amazing shapes while performing their mating displays—very appealing to an artist whose work is all about form.

Nicholls watched video of the birds over and over from many angles and pored over photos. He borrowed study skins from the Royal Ontario museum. The largest piece, showing a Greater Bird-of-Paradise in a mating dance, took nearly 300 hours to create.

“I was trying to capture the extreme,” Nicholls explains. “How far does that gesture go? When that parotia is doing its dance, there’s a maximum position and if I can catch that, I can create a very dynamic silhouette.”

Bird-of-paradise or Black-capped Chickadee—every sculpture starts with a vision, often an attempt to capture a precise moment or a special memory. The vision becomes a sketch. Nicholls spends many solitary hours sketching and refining in his attic studio, the walls adorned with the crayon drawings his children made when they were little. The final sketch is the road map for all that follows. He partitions the sketch into layers, subdividing the drawing into individual pattern pieces which will be transferred to the paper, then cut, and glued to the body shape. Nicholls uses special tools to create cuts, scores, curls, and bends in the paper that toy with light from every angle.

“What makes the sculptures work is thinking about anatomy and how fur and feathers flow a certain way on the musculoskeletal structure,” says Nicholls. “I have to get a sense of the skeleton and the muscles and what they do in certain gestures.” Understanding the underlying body structure is especially important in mammals with short coats, Nicholls says, where he must accurately catch the changing landscape as muscle and bone define the shape of the body at rest or in motion.

The paper itself is just as important as the research and planning. “I use 100 percent cotton archival paper in multiple thicknesses,” Nicholls says. “I can do the fine hairs on mammals or the fine underwing coverts and the really fluffy stuff on birds with the lighter-weight paper but use the heavier paper for the structure and for beaks and legs.”

Archival paper doesn’t contain lignin, a substance found in the cell walls of most other plant-based papers and which causes it to turn brittle and yellow over time. These works of art are meant to be passed down through generations. Because there are so few colored papers of archival quality, Nicholls creates his sculptures primarily in white, but does introduce pale washes of color in some pieces for additional pop. He’s begun working with some new papers with fiber structure that makes them very strong. He used this paper in a sculpture of a Gray Crowned-Crane, an elegant but endangered African species with a powderpuff crest.

“I wanted the crown to shimmer, so I used Japanese handmade papers in different shades and weights and it created a neat effect, it’s one of my favorites,” says Nicholls. This piece has been featured in the annual Birds in Art show in Wisconsin.

Though Nicholls has become known for his beautiful, award-winning sculptures, he hasn’t forgotten about the camera. Initially he used an old-fashioned large format bellows camera to capture photos on film. Now he relies on top-of-the-line lenses and digital cameras so that images can be enlarged and reproduced as limited-edition prints. Despite the solitary nature of his work, Nicholls says he loves the collaboration with clients and with experts on exotic species. The work always seems to open doors to new people and possibilities, “keeping the adventure alive.”

“I have the same enthusiasm for what I’m doing that I did when I started because the possibilities are absolutely endless,” Nicholls says. “The satisfaction comes in different ways. It can be right at the art table, seeing how the light and shadow are working while I build a piece. And it can be meeting others who have somehow chosen me to capture a special moment or memory for them in this form—it’s an honor.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library