New BirdCast Analysis Shows How High Migrating Birds Fly

By Gustave Axelson

October 13, 2021

From the Autumn 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

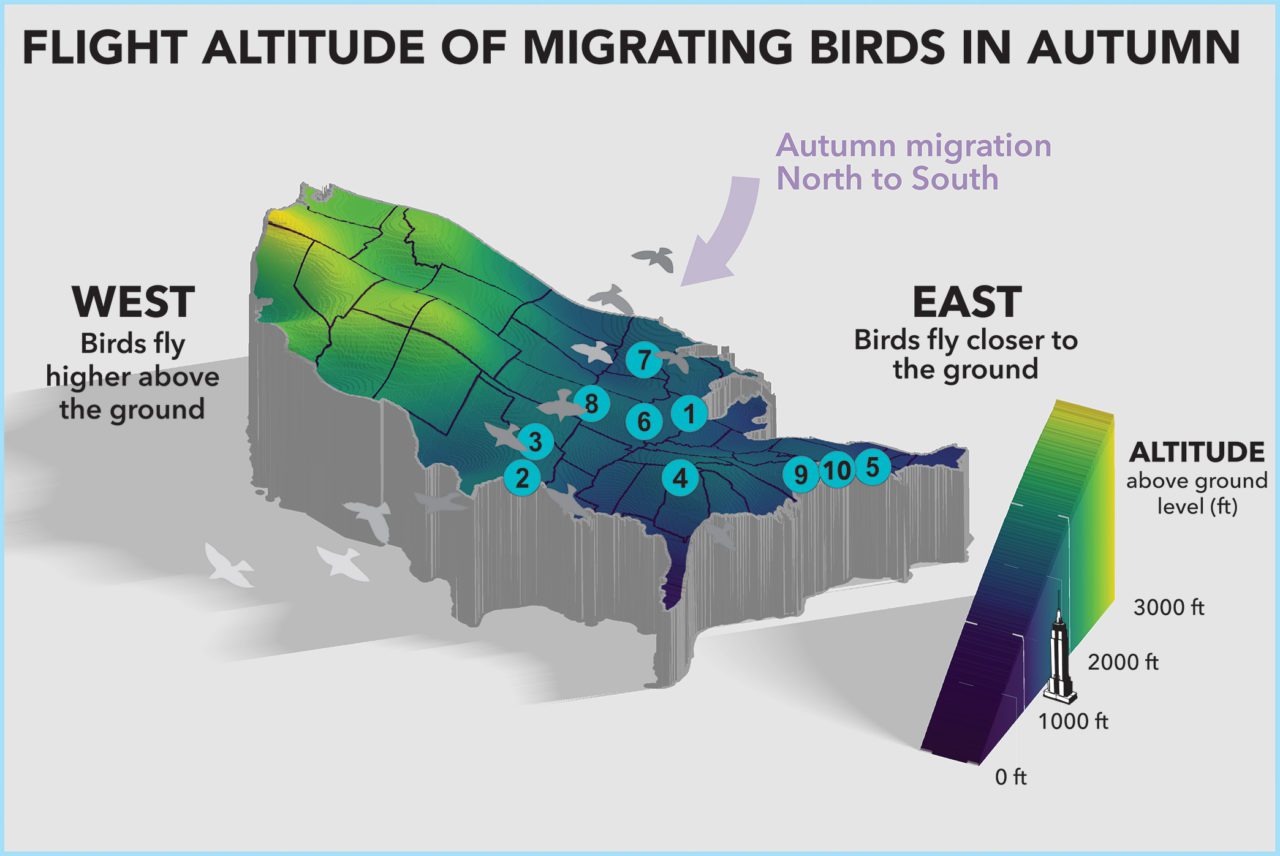

Billions of birds will take to the skies on southbound migration throughout the United States this autumn. While they’re all headed south, they’ll take different aerial routes, and they’ll even fly at different altitudes. A new analysis by the BirdCast team—a partnership between the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Colorado State University, and University of Massachusetts Amherst that uses weather radar to monitor and predict bird migration—shows striking differences in the flight altitudes of migratory birds from the East to the West.

The analysis used radar data from 143 weather-monitoring stations across the U.S. to measure bird flight altitudes above the earth’s surface. In the East, average flight heights in autumn for migratory birds in New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia were about 400 to 500 meters (or about 1,300 to 1,600 feet) above ground. Fall migration altitudes were lowest in New England, Michigan, and Florida. In the West, fall migratory bird flights in Washington, Oregon, and California averaged around 800 meters (or about 2,600 feet) high, but many birds flew even higher—with the highest flights reaching 5,000 to 6,000 feet in altitude.

According to Adriaan Dokter, a Cornell Lab research associate and expert in radar ornithology who led the analysis for the BirdCast project, the varying levels among bird flight altitudes are mostly driven by a common factor—tailwinds.

“A lot of these differences have to do with prevailing wind patterns,” Dokter says. “Birds have a remarkable talent to find the altitude layers where they can get a free ride on the wind and avoid altitude layers with opposing winds.”

Frank La Sorte, another Cornell Lab research associate who has had several research studies published on bird migration using eBird and radar data, says topography may also play a role in pushing flight altitudes higher in the mountainous West.

“Another factor could be the greater topographic heterogeneity in the West, which may result in birds climbing to higher altitudes to clear mountains,” says La Sorte. “After expending energy to gain altitude, they may then maintain those altitudes for the entire trip, likely to avoid having to expend additional energy if another mountain is encountered.”

The eastern half of the United States—where birds tend to fly at lower altitudes on migration—is a risky area for bird mortalities from building collisions. Another BirdCast team analysis published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment in April 2019 showed that the 10 most dangerous cities for migrating birds in fall are all east of the Great Plains.

This autumn, lights-out initiatives in Chicago, New York City, and Philadelphia will dim city lights and reduce building collision risk for migratory birds. Eight Texas cities—including Houston and Dallas—will participate in BirdCast’s Lights Out Texas initiative to dim urban lights on peak bird migration nights across the Lone Star State.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library