Is Bird Migration Getting More Dangerous?

April 1, 2021From the Spring 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Imagine walking coast-to-coast across the United States and back—6,000 miles—over the span of a few weeks, using nothing but your own body power. Now imagine you are the size of a lime. That’s akin to what some Blackpoll Warblers face as they start off from Colombia each spring on the way north to breeding grounds in the boreal forest.

Despite the grueling trip, blackpolls are among the most abundant warblers within their vast breeding range, which stretches from New England to the Maritime Provinces of Canada and across the continent to Alaska. But this once-robust population is crumbling, suffering a 90% loss in the last 50 years. Today there are tens of millions of blackpolls embarking on spring migration, whereas in the mid-20th century there may have been hundreds of millions.

While that blackpoll decline is eye-popping, it’s just one of many distressing stories from research published in the journal Science in 2019 that documented the loss of 3 billion breeding birds in North America since 1970. More than 80% of those losses were among migratory birds, says Ken Rosenberg, senior conservation scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and one of the lead researchers of the paper.

“We know migration is the most dangerous time of year. Lots of birds don’t make it,” Rosenberg says, noting that spring and fall have the highest rates of avian mortality. And, he says, the longer the migration, the more dangerous: “The risk seems to increase on a per-mile and per-day basis.”

Rosenberg notes that migratory birds have persisted through ice ages and shifting continents for hundreds of thousands of years. But the challenges migratory birds face today are not the same as they were thousands of years ago—or even decades ago.

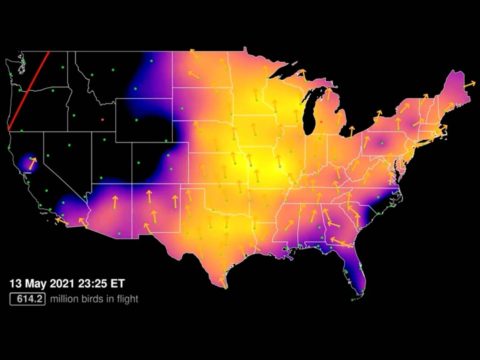

“There are more people, more structures, more lights, more weather. And the changes seem to be speeding up,” says Andrew Farnsworth, a senior research associate at the Cornell Lab and project leader for the BirdCast program that studies bird migration via weather radar. According to Farnsworth, addressing these new threats is key to turning around the larger loss of 3 billion birds: “Finding out what happens to birds during these migrations has to be a focus if conservation measures are going to be effective.”

The good news is that in the past decade, there has been a rapid rise in new research methods and new technologies to study and understand bird migration—and a growing group of scientists like Rosenberg and Farnsworth dedicated to creating safer passage for migratory birds.

Migration: the Ultimate Journey

Migration is an exhausting and uncertain undertaking—but judging by the thousands of bird species worldwide that have evolved to migrate, it’s a gamble that seems to pay off. Bird migration capitalizes on seasonal surges in protein and nutrients—like insect hatches and fruiting seasons—that are needed for breeding. These globe-spanning voyages might seem extreme, but most migratory birds don’t make their entire journey in one trip. Instead, they play a game of hemispheric hopscotch, skipping from one migratory stopover site to the next, like a family minivan hitting rest stops on a cross-country road trip.

As Gray-cheeked Thrushes migrate from South America to the boreal forest in spring, they often stop for a week or more in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains of northern Colombia to feast on the abundant fruits.

“We used to think these birds would stop somewhat at random, but now we know birds heading north are concentrating at a few places for longer, places that really have the resources they count on,” says Cornell Lab postdoctoral researcher Camila Gomez, who tracked Gray-cheeked Thrush migration over two years in 2015 and 2016. Gomez says that over the course of their migration, the Gray-cheeked Thrushes she studied spent much more time on the ground at stopover sites than in the air—about 10 days fueling up at a stopover for every two or three days of actual flight.

“So 70% to 80% of the time…will likely be spent at a few critical locations like the Sierra,” she says. “Birds have been relying on these kinds of spots since prehistory, relying on peak resources to be there at the right time. So when those conditions change—if a place is logged, or if timing of an important food resource changes, the birds can’t always get what they need.”

Gomez says most of the area around the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains was converted to agriculture decades ago. Thankfully, parts of this key stopover lie within Colombia’s second-oldest national park, protected since the mid-1960s. The protected sites benefit thrushes as well as other long-distance migrants that use the site, such as Veeries, Tennessee and Blackburnian Warblers, and Red-eyed Vireos. But, Gomez says, clearing for agriculture is eating away at other important stopover sites elsewhere in South and Central America.

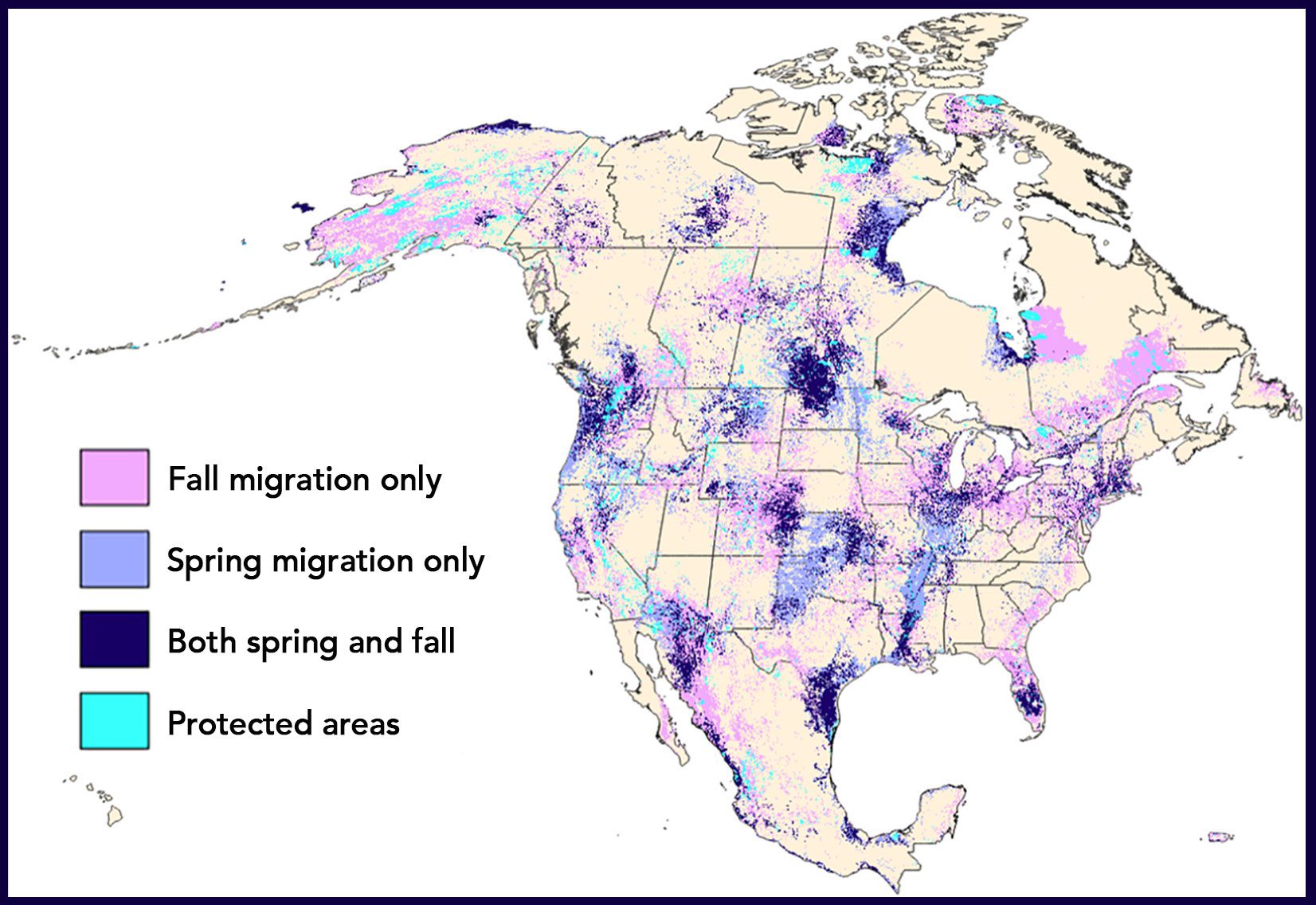

Amanda Rodewald, senior director of the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab, says that prioritizing the lands that are most important to birds on migration can guide conservation efforts to be more strategic and effective.

In 2019, Rodewald was part of an international research team that used the Cornell Lab’s eBird database to identify the most important areas in the Western Hemisphere for over 100 Neotropical migratory songbird species across their entire breeding, migratory, and wintering ranges. A second study in 2020 revealed that nearly half of priority stopover sites occur within human-dominated landscapes—and that fewer than 10% are protected.

“These kinds of models are game-changers for decision-makers, managers, and landowners who want to protect migratory birds in regions where land is already in high demand for other uses,” Rodewald says. She points out that it’s much more cost-effective to protect a stopover site than an entire landscape. “We can reduce the overall cost of conservation, but while maximizing positive outcomes. We can accomplish more with less.”

Light Pollution and Migration

While long-distance migratory birds use their stopover habitats by day, for many, the actual miles clocked happen under the cover of darkness.

This strategy of migrating by night—when there are fewer predators, fairer winds, and cool damp air that minimizes water loss—has worked wonderfully for birds for millennia. On clear nights, nocturnal migration had the added perk of allowing birds to use the starry sky as a navigational aid.

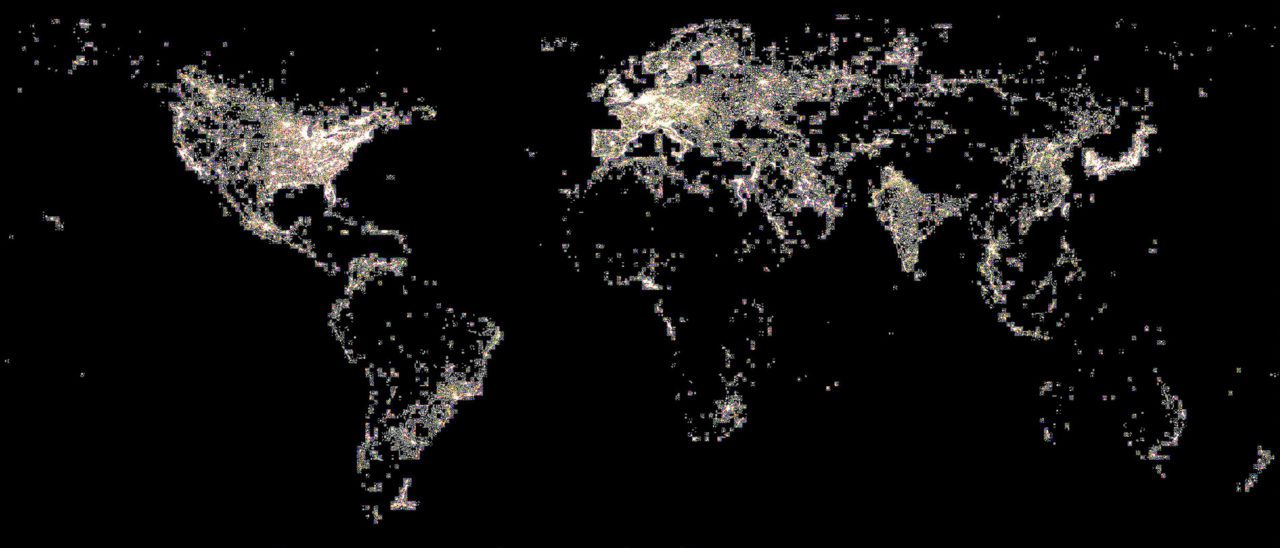

But within the past century, birds’ stellar view has faded. About a third of the world’s human population lives in places where they can no longer see the Milky Way, and light pollution continues to increase by around 2% per year. Instead, a different set of constellations has sprung up from terra firma—billions of artificial lights beckoning brightly from below as they dim the view above.

“[Birds] are being disoriented, pulled into cities, and they’re being set up for a less successful stopover,” says Kyle Horton, a collaborator on the BirdCast program who heads up the Aeroecology Lab at Colorado State University. Horton says that migratory birds drawn into urban areas by bright lights at night are being lured into a suboptimal stopover. “Cities generally have less [tree] cover and fewer native plants, which equals less food. While people may enjoy seeing migratory birds appear in urban areas, it’s probably not good for bird populations.”

A few years ago when Horton was a postdoctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab, he was part of a project with New York City Audubon that revealed more than 1 million birds were drawn into NYC over seven nights by the mile-high beams of light pointed skyward at the Tribute in Light, a memorial to 9/11 victims in Lower Manhattan. The beams caused the birds to circle pointlessly for hours. By studying weather radar data, Horton and fellow scientists could also tell that migrating birds in the region were being pulled toward Lower Manhattan and the Tribute, and away from their regular routes. The research helped inform a collaboration with the National 9/11 Memorial & Museum to dim the beams periodically to allow concentrated birds to disperse.

NYC isn’t the only source of light pollution. Last year, Horton and Cornell Lab research ecologist Frank La Sorte analyzed eBird data and found that migrating birds are being drawn toward cities all across North America. The persistent nightly glow of large cities may be altering birds’ migration behavior on a grand scale.

“Birds are showing up at higher than-expected levels during both spring and fall migration,” says Horton. “Beyond the immediate danger of cars and buildings and predators, stopping in urban areas could be altering or slowing their migration routes in ways that could have consequences for birds throughout the rest of the year.”

Chicago was named the most dangerous city in America for birds on migration, based on radar and light-pollution data. The city also (unfortunately) has incredibly robust data on bird collisions—over 100,000 dead birds meticulously collected and cataloged in spring and fall from the past four decades.

Because of intensive monitoring at the site, around 40,000 of these dead birds have been collected at just one building—McCormick Place, a glass-facaded convention center in Chicago’s South Loop. Perched on the edge of Lake Michigan, it’s been a mortal magnet for birds migrating along the shores of the Great Lake, and a rich source of study material.

Dave Willard, former collections manager for Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, started collecting dead birds at McCormick Place in 1978. He says that while bird fatalities still occur there regularly, the numbers dropped from thousands of birds a year to hundreds per year when the building began turning off the lights at night in the early 2000s.

The McCormick Place bird-collision data is incredibly detailed, noting not only which window each bird hit over the years, but whether the lights in that window were on or off. Cornell postdoctoral researcher Benjamin Van Doren worked with Willard and others on a forthcoming study that shows for the first time the significance of a single window bay. Van Doren found that not only is a darkened window bay much less likely to sustain a bird impact at night than lit windows, but the windows surrounding an unlit window bay are also slightly less likely to incur collisions—even when illuminated. This means birds are not simply avoiding some windows only to hit other ones.

“Colliding birds appear to be attracted to specific light sources, not simply disoriented by overall city or sky glow,” says Van Doren. “So even if an area is otherwise brightly lit, darkening a single window bay is likely to decrease the number of collisions.”

Since 1995 Chicago Audubon has managed a Lights Out program in the city, advocating for buildings within the Loop area to turn off or dim their lights during spring and fall. But Dave Willard suspects that with all the new downtown construction in recent years, the overall bird fatality rate in the city may be going up. He is hopeful that Van Doren’s new research will make it easier to convince people that simple actions can have major benefits.

The Hunt Headquarters in Dallas with its lights on. The building was part of the Lights Out Texas initiative and dimmed its light during peak migration. Photo by Lloyd and Melissa Clayton.

The Hunt Headquarters with its lights off. This was one of the buildings in Dallas that dimmed its lights in fall 2020 during peak bird migration. Photos by Lloyd and Melissa Clayton.

Around Dallas, Texas—another urban center on the list of most dangerous cities for migrating birds—several downtown residents and building owners took a simple step last October when they responded to calls from Mayor Eric Johnson and former First Lady Laura Bush to turn out nonessential lights at night. The public announcements were timed for the peak days of fall bird migration, when more than 1 billion birds fly through Texas. The PSAs in newspapers and on social media were part of a new initiative from BirdCast called Lights Out Texas that’s aiming to shine a light on the benefits of darkness for migrating birds.

And they worked. Some of Dallas’s most iconic downtown buildings—such as City Hall, the Dallas Zoo, and the AT&T Discovery District—pulled the plug on their decorative lighting for a week. This spring, Lights Out Texas has put out another call to dim the lights in Dallas from mid-April to early May, when a billion birds will be migrating through the area again. And this time, the call will go to other Texas cities as well.

“We’re now talking to folks in cities all across the state who took notice of Dallas’s participation last fall,” says Lights Out Texas coordinator Julia Wang. “Having widespread buy-in across Texas, a place we know is so important for migratory birds, would be an extremely valuable boost for the movement nationwide.”

Adverse Unpredictable Weather and Migration

As the sun set on October 1, 2020, millions of birds migrating along the Atlantic Flyway had a green light: clear skies, a full moon, and favorable northwest winds.

But the weather en route was less favorable. Over the course of the night, a line of low clouds and showers pushed east toward New England and the Mid-Atlantic coast. The next morning, volunteers for Philadelphia Audubon discovered 400 dead and dying birds across three city blocks, including Black-and-white and Black-throated Blue Warblers, Northern Parulas, Ovenbirds, thrushes, and sparrows.

Learn More About Migration

“So many birds were falling out of the sky, we didn’t know what was going on,” one of the volunteers told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It was catastrophic.”

Adriaan Dokter, a Cornell Lab researcher who uses weather radar to study bird migration across the Western Hemisphere, says that the low clouds may have caused the birds to be disoriented and fly into the buildings.

“It seems to be often this combination of very strong migration and unexpected adverse weather that leads to the mass mortality events in cities,” Dokter says.

And sometimes bad weather can impair bird migration away from urban areas, as illustrated by events in the southwestern U.S. last fall.

“The weirdness started in August, really,” says Martha Desmond, a scientist and professor at New Mexico State University–Las Cruces. “People were reporting very odd bird behavior across New Mexico. Birds were crawling under buildings, running out into roads…more roadkill birds than I’ve ever seen.”

Starting in early September, it seemed as if birds were dropping left and right: dozens of dead birds along a city bike path; a group of flycatchers and Barn Swallows in a suburban park. In an arroyo north of Albuquerque, 258 Violet-green Swallows and dozens of Wilson’s Warblers dropped dead.

On September 7, the city of Albuquerque set a record high temperature for the date, 97°F. Just two days later, early morning temps bottomed out at 39°F—a record low. The 60-degree drop resulted from a cold front that barreled through the region with high winds, snow, and freezing rain. Over the next week, more than 1,000 dead birds were reported throughout New Mexico and surrounding states. Rough estimates of total bird deaths in the region ranged from thousands to hundreds of thousands.

Examinations of dead birds collected at multiple locations all pointed to one common factor—the birds were starving. Andrew Farnsworth thinks it was probably a combination of weather- and climate-related factors that led to the high body count.

“New Mexico had the hottest August on record, the West had the worst fire season on record, and the region is in the middle of its worst drought in 20 years, so insect populations were going to be way down already,” says Farnsworth. “Then there’s this anomalous early snowfall following record temperature swings. All of that equates to stress on the birds’ bodies and a lack of food during a time when they really need it.”

A 2015 study found that reported mass mortality events for birds as a group trended upward from 1940 to 2000, with weather events far and away the most common cause. And the weather is getting worse. The 2018 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change documents how a changing climate is causing more intense weather-related events around the globe—more intense rain and snow events, more droughts, more floods, more heat waves, more storm surges.

And it isn’t just severe weather events, but the bigger picture of accelerating climate change that is poised to wreak havoc with long-distance bird migrations. A 2019 study using 24 years of radar data found that spring migrations across all bird species are shifting earlier by almost two days every decade.

Try the 7 Simple Actions

“Bird migration over the past few millennia has developed under a set of climate conditions that was relatively unchanging, and migrating birds have been able to minimize their time, energy, and risk,” says the Cornell Lab’s Frank La Sorte, one of the coauthors of the study. “If these conditions change quickly, these patterns are disrupted and the risks are going to go up.”

Another study led by La Sorte also predicts that winds in the Northern Hemisphere in spring and fall will come out of the south more often as the temperatures rise. While that could hamper birds traveling south in the fall by creating a headwind, it could benefit birds in spring by helping them reach their destinations with more of their energy stores intact. Since timely arrival on breeding grounds is important to breeding success, La Sorte thinks the wind shifts could end up being a net benefit.

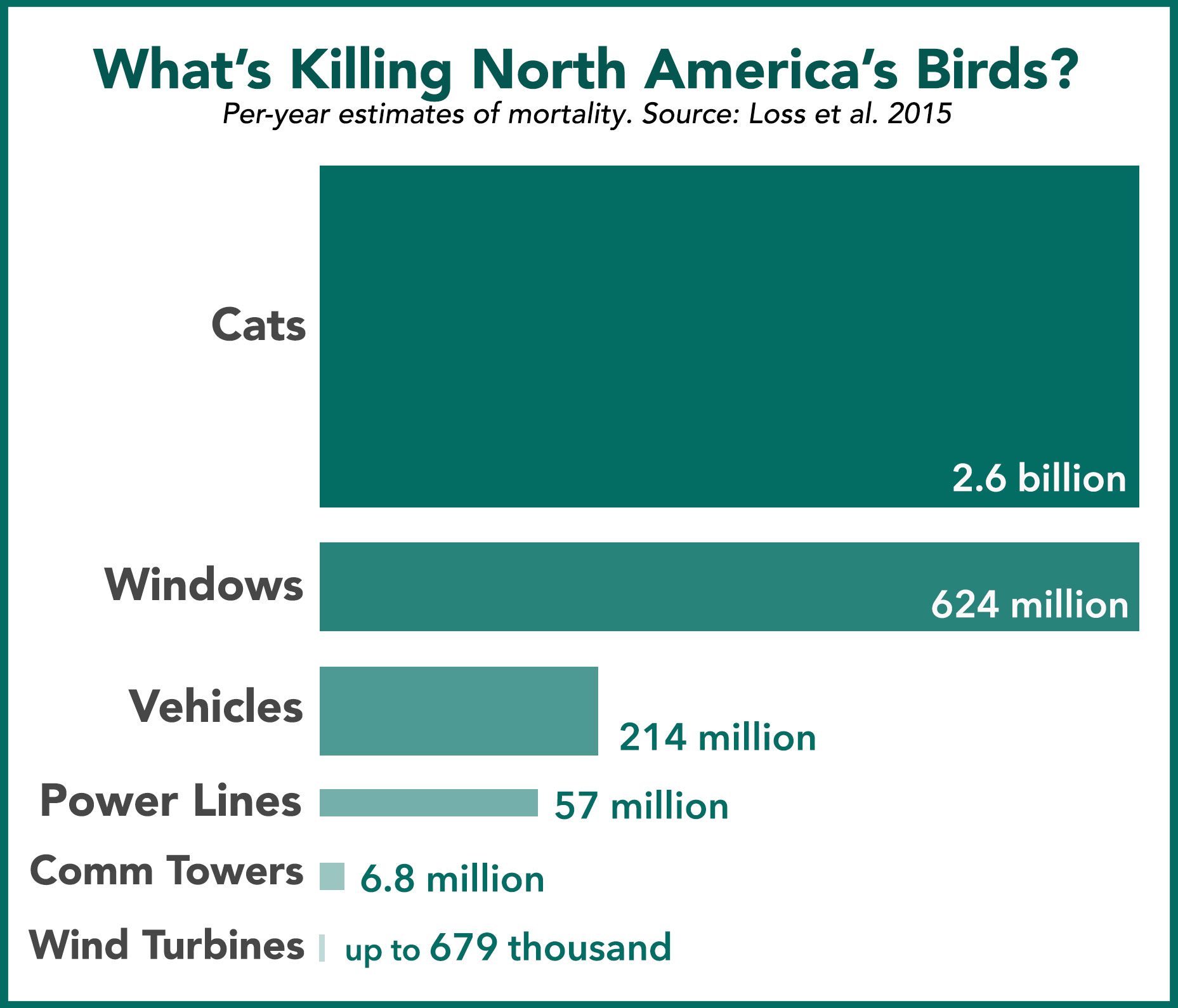

While the future for bird migration is somewhat uncertain, Amanda Rodewald says we already know many ways that people can make it safer. Her punch list of priority conservation actions includes restoring ecologically degraded migratory stopover sites, developing incentives to protect sites on private lands, implementing public outreach campaigns like Lights Out and Keep Cats Indoors programs that reduce threats to birds on migration, and working to reduce the exposure to chemicals and pollution that can weaken the body condition of long-distance migratory birds.

“The threats are real; the declines are real,” Rodewald says. “We must take action in as many ways as possible.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library