Glass Action: Advances in the Science of Making Windows Safer for Birds

By Pat Leonard

January 15, 2013

It happens all the time. A dull thud at the window, a few feathers clinging to the glass, and a bird lies stricken on the ground below. If you’re lucky, the bird revives in a few minutes and carries on with its life. But far more often it dies right there, joining an estimated 365 million to a billion birds killed each year by window collisions in the United States alone. (An estimated 25 million birds die annually from window collisions in Canada.)

The latest U. S. numbers come from Scott Loss of Oklahoma State University. He and collaborators at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service just published a two-year study in The Condor: Ornithological Applications in which he calculated the overall death rate from window strikes. Based on the data, Loss believes the total could be as high as 1.3 billion birds killed each year.

To come up with the latest figures, Loss extracted data from 23 existing studies. “We used both peer-reviewed publications and unpublished data collected by citizen scientists engaged in building monitoring programs in large cities,” Loss explains.

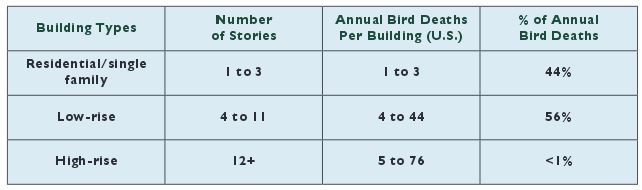

He also looked at building types. Although bird kills at high-rise buildings get much of the attention, Loss finds that the vast majority of annual bird deaths can be traced to residential and low-rise structures. An average single-family residence is estimated to kill one to three birds each year, but when you multiply that figure by the huge number of homes in this country, Loss says a midrange estimate of 253 million bird deaths can be attributed to houses.

The estimated annual range of bird mortality remains very broad for both low- and high-rise buildings. That’s because a complicated tapestry of environmental and structural variables gives each building its own unique potential to kill birds.

“A major part of our study was also to see which species were disproportionately vulnerable to collisions,” says Loss. After controlling for the abundance of a species in a given location, Loss found six that seemed to strike windows more often than would be expected by chance at every building type: the Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Brown Creeper, Ovenbird, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Gray Catbird, and Black-and-white Warbler. Neotropical migrants were found to be more vulnerable at low- and high-rise buildings, possibly because of exposure to more structures along their route, unfamiliarity with a location, and attraction to buildings that are kept lit at night. Some of these vulnerable species are listed as threatened or have declining populations, Loss points out, including the Golden-winged Warbler, Painted Bunting, Canada Warbler, Wood Thrush, Kentucky Warbler, and Worm-eating Warbler.

Finding what works to save birds is Daniel Klem, Jr.’s, life’s work.The Muhlenberg College professor has been studying bird-window collisions for 40 years. He invented the collision-avoidance test-tunnel methodology, which he used in experiments at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale during the 1970s. Dark-eyed Juncos were released into a tunnel with one clear glass pane and an open-air pane side-by-side at the escape end. These experiments firmly established that birds don’t see glass, failing to pick up structural cues that humans use to recognize there’s a barrier. (Without cues such as window frames and building walls, the human eye cannot see glass either. The Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which collects injury data from hospital emergency departments across the United States, estimates there were 151,435 accidents involving glass doors, windows, and panels in 2012.)

Two properties of glass make it lethal for birds. Glass can appear completely transparent. Glass walkways between buildings are especially deadly because birds spot greenery on the other side and try to fly straight through. Glass can also be a mirror, reflecting the sky and surrounding vegetation, creating the illusion that the habitat continues.

Some glass manufacturers are now glazing windows with patterns that reflect ultraviolet light, which most birds can see—an important exception being raptors. Evaluating the effectiveness of these new glass types is complicated. Building orientation, weather, time of day, time of year, landscaping, inside light levels, and other factors all influence how birds perceive glass and any patterns applied to it.

An early developer of commercial bird-friendly UV glass is ArnoldGlas of Germany. Their Ornilux product was introduced to North America a few years ago, although it is currently only manufactured in Europe. The most recent version, Ornilux Mikado, uses a random “pick-up sticks” pattern of UV-reflecting and UV-absorbing glaze to break up reflections to reduce bird collisions. UV light must be reflected for a bird to see it. To humans, the glass looks clear.

Does it work? Christine Sheppard heads the Bird Collision Campaign for the American Bird Conservancy (ABC) and has tunnel-tested Ornilux Mikado at the Carnegie Museum’s Powdermill Avian Research Center, near Pittsburgh. In those tests Sheppard says the Ornilux UV glass was “moderately effective.” Klem field-tested Ornilux Mikado but found no significant difference in the number of bird strikes as compared with a regular glass pane and a reflective glass pane used in the experiment.

Research and development is ongoing at ArnoldGlas. According to Lisa Welch, the company’s market development representative in the United States, the company creates new prototypes each year for tunnel-testing by the American Bird Conservancy and by a flight tunnel facility in Rybachy, Russia. “Our close cooperation with the ornithologists testing for us and their analysis is critical to improvements,” says Welch. “We hope that as awareness of the collision issue grows and more cities adopt design guidelines, the market for these glass types will also grow.”

Though Klem believes tunnel-testing is a valuable way to assess collision-prevention methods quickly, he says complementary outdoor field-testing is essential. In a recent scientific paper in The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, he says tunnel tests address the transparency problem but not the reflective property of glass and cannot simulate windows in actual buildings the way field tests do.

Meanwhile, Sheppard is working to improve tunnel protocols and testing a brand new tunnel built inside a large metal shipping container on the grounds of the Bronx Zoo. Some of the information she’s hoping to gather includes whether birds see and react to netting placed in front of the windowpanes to prevent bird deaths during tests. She’s also looking into whether a daylight simulator will provide more accurate results compared with light bounced off mirrors.

Klem found that most birds will avoid windows with a pattern of vertical stripes spaced four inches apart, or horizontal stripes spaced two inches apart and placed on the outside of the glass.

Sheppard has also tested an insulated glass product that has a pattern of 1/8 -inch white ceramic dots, or “frit,” on the inside surface of the window. With 20 percent of the glass covered with an array of dots, she found 59 percent of the test birds did not fly toward that window, but to the clear, untreated pane; with 40 percent window coverage, 75 percent of the test birds stayed away from the patterned pane. When dots were consolidated as 1/8-inch-wide vertical or horizontal lines separated by a 1/2-inch, more than 90 percent of birds flew toward the clear control pane. Sheppard says arrays are harder for birds to see than lines.

Research by Klem in 1979 and in 1990 produced the so-called “2 x 4” rule governing how patterns may best be applied to glass to deter bird collisions. He found that most birds will avoid windows with a pattern of vertical stripes spaced four inches apart, or horizontal stripes spaced two inches apart and placed on the outside of the glass. Inside patterns can be completely obscured by strong reflections on the outside surface of the window.

The Ornilux Mikado UV-patterned glass is one kind of window collision-avoidance glass. Photo courtesy of Arnoldglas.

Window glass using horizontal stripes is another kind of collision-avoidance glass. Photo courtesy of Martin Rossler.

These pattern results were later duplicated with European birds in studies done by Martin Rössler of Austria. He also found the most effective pattern to be Plexiglas with embedded horizontal polyamide filaments placed 28mm apart. Rössler and his coauthors concluded that this pattern was highly effective even though it covered only 6.7 percent of the glass surface.

Both Klem and Sheppard say they are seeing more interest in the new UV-patterned glass and retrofit window films from architects, planners, and builders as well as government entities at the local, state, and federal level. The U. S. General Services Administration (GSA) is required to use sustainable design in new federal buildings. Sheppard says the GSA is now incorporating bird-friendly features in its building guidelines, which are currently being revised. “Green” building guidelines with bird-friendly provisions (some voluntary, some mandatory) have been adopted in San Francisco, Oakland, Portland (Oregon), Toronto, and the State of Minnesota. Lisa Welch of Ornilux says the company’s products have been installed in a number of high-profile projects, such as a new science building at the University of Massachusetts, a polar bear exhibit at the North Carolina Zoo, a restaurant on the Santa Monica Pier, and a visitor center for a U. S. Fish and Wildlife facility in Maryland. A bill to establish a Federal Bird-Safe Buildings Act has been introduced to the House of Representatives three times, but so far has not gotten out of committee

Both carrot and stick strategies are being used to encourage sustainable building design. For example, the U. S. Green Building Council runs the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design program (LEED). Building projects that satisfy specific requirements earn points that lead to bronze, silver, gold, or platinum certification. Initially, the LEED guidelines, or credits, were primarily focused on energy savings so, as Klem points out, “You could have a platinum-rated building that is killing large numbers of birds.”

The Green Building Council is now pilot-testing a new LEED credit that requires a building’s design to include window-strike deterrents to protect birds.Though still in its beta stage, the Council says that, as of this writing, 56 applicants have implemented or are attempting to implement the credit in their projects, and at least another 52 projects are in the pipeline. However, Klem worries that bird-friendly industry standards for glass are based entirely on tunnel-testing results, and he continues to advocate adding field testing before drawing conclusions about effective ways to prevent collisions.

In Canada, a nonprofit group of environmental lawyers called Ecojustice is using the stick approach. They are filing lawsuits against building owners, charging them with violating the country’s Species at Risk Act and provincial laws protecting birds. Ecojustice sued Cadillac Fairview, owner of a north Toronto office complex, accusing the company of violating the Ontario Environmental Protection Act because of bird collision deaths. The judge eventually dismissed the case after Cadillac Fairview installed anticollision film on its windows but agreed that window kills violate Canada’s environmental statutes protecting birds, setting an important legal precedent. Klem believes the same legal tactic must be part of the fight in the United States.

Though inroads are being made in large-building design, it is equally vital to focus on residential construction. “There may be only a few birds killed at each home per year,” says Klem, “but the killing adds up, it goes on year round, and it is indiscriminate, taking healthy birds out of the population.”There’s also unknown “collateral” damage when adult birds are killed during the breeding season and cannot return to their nest to feed and care for their chicks. There are simple ways to reduce window strikes at existing homes.

“We’re at a point where we’re making some progress, but it’s limited,” says Klem, who continues to field test glass-avoidance products and window patterns. “I think the architectural community is paying more attention and there’s more awareness. But it’s not to the point where there’s a critical mass of people who are actually doing something, and all these bird deaths are an insidious erosion of the health of bird populations.”

“Part of what scares me is that right now we’re simply trying to slow the rate of increase in the use of glass for construction and renovation,” Sheppard says. “We need birds. They perform vital functions in ecological systems.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library