Get to Know Your Bird Families With a New Handbook

By David W. Winkler

From the Winter 2016 issue of Living Bird magazine.

January 26, 2016

If you’re a birder, you’re probably already captivated by birds in all their amazing forms—from the insect-like glimmer of a hummer’s wing to the sleek submarine cruising of a merganser swimming by. Birds come in a great variety of shapes and sizes and have a wonderful array of ways to make a living.

Many birders dive into the world of birds by answering the simple question: “What species of bird is that?” It would be quite a tall order to familiarize yourself with all 10,000-plus species of birds alive on earth today. But for centuries biologists have made it possible to learn all the major kinds of birds. By placing similar birds in the same taxonomic families, biologists sort birds by their shared fundamental characteristics—how they are built, how they act and raise their offspring, and how they make a living.

It is no accident that most good field guides are still organized by families. By placing birds from the same family on the same pages, field guide authors place most similar birds together and they thus focus on the contrasts between the species. Thus, you can make quick use of a field guide if you already know your families. Say you’re birding in Venezuela for the first time and you see a bird in the short grass next to some cattle, picking up insects that the cows scare up as they walk. It’s acting like a robin, but you get a good enough look to see the face—a sharper bill and an angular face that suggest the kingbirds back home. Knowing that kingbirds are part of the huge tyrant flycatcher family Tyrannidae, you thumb to the flycatcher section of your field guide, and zoom, there it is: a Cattle Tyrant.

“Memorize all the world’s avian taxonomic families and you’ll enjoy faster bird ids and a global appreciation for bird diversity.”

For decades, I have been making my ornithology students in Cornell University’s upper-division ornithology class learn the taxonomic families of birds of the world. I’m told it’s the hardest part of the course. But it is also the part of the course about which I’ve received the most praise from alumni. Students who have gone on to careers in ornithology are often grateful that the course left them with a mental framework for storing generalizations about different groups of birds, generalizations that allow them to anticipate the behavior and biology of a member of a family that is new to them and to recognize exceptional idiosyncrasies of a bird that don’t quite fit with others in its family. Even alumni who don’t pursue ornithology as a career find this knowledge valuable. I’ve had past students tell me that they were vacationing in Sydney or Singapore and were gratified that they recognized many of the birds around them as soon as they arrived.

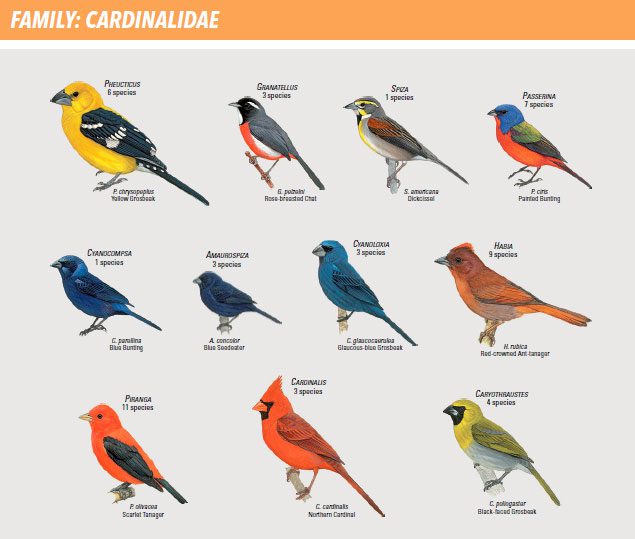

Even close to home, knowing your families will enrich your appreciation of birds. When you look out the kitchen window at your bird feeder and see chickadees (Paridae), nuthatches (Sittidae), jays (Corvidae), and cardinals (Cardinalidae) you’ll see not just individual species but the grand structure of the bird community in your backyard. You’ll know that each of these comes from a different large trunk in the family tree of songbirds, each of which has a distinct evolutionary history and geographic origin. And you’ll know that a similar look out a window in Europe could have a very similar set of species with very similar families, though the cardinals would be replaced there by a finch (Fringillidae) or a bunting (Emberizidae).

Once you have an appreciation of the families of birds of the world, you have a comprehensive understanding of all the basic kinds of birds on earth. Every bird you encounter becomes richer. You come to appreciate how every species is a variation, some subtle, others more abrupt, from the general theme that applies to all members of its family. You can appreciate how new and strange any given bird might seem to a bird lover from another continent, and how birds from other families play similar roles in habitats elsewhere. You’re better prepared for birding when you travel abroad, and yet you can also think globally when you bird locally.

Want to bird at an entirely different level? Then do your homework: Learn your families!

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library