George Archibald Wins Arthur A. Allen Award

By Marc Devokaitis

September 19, 2018

From the Autumn 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

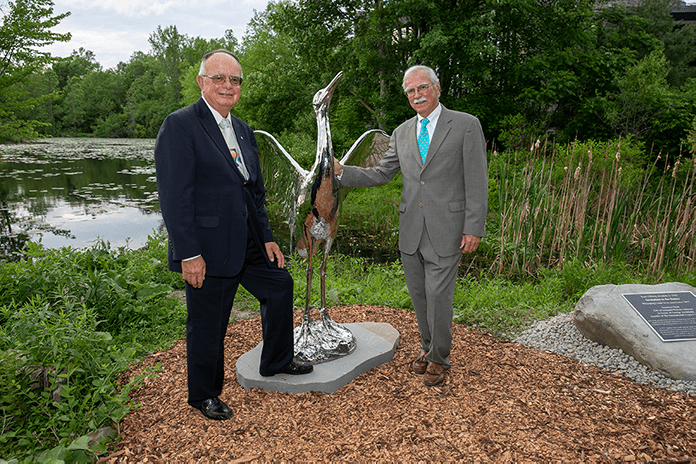

In a ceremony at Sapsucker Woods on May 31, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology honored George Archibald with the Arthur A. Allen Award. Established in 1967, the award is named after the Cornell Lab’s founder and honors those who have made significant contributions to ornithology, while making the science of birds accessible to the public. Past winners of the Arthur A. Allen Award include Roger Tory Peterson, Alexander Wetmore, Victor Emanuel, Tom Cade, and Linda Macaulay. Archibald has dedicated his life to the conservation of the world’s cranes, working for nearly five decades as cofounder, director, and now senior conservationist at the International Crane Foundation.

“For a generation of ardent conservationists, George has represented one of the most dedicated, passionate, inspiring, focused, tireless, and inclusive practitioners any of us has ever met,” said Cornell Lab director John Fitzpatrick during the ceremony. Archibald’s life with cranes took off when he arrived at Cornell University as a graduate student in 1968. He quickly converted a dilapidated former mink barn at Sapsucker Woods into a crane research facility, housing nine of the 15 species of cranes from around the world to study their behavioral displays. When the barn was scheduled for demolition, Archibald and fellow Cornell student Ron Sauey hatched a plan to continue their work in barns on Sauey’s family property in Baraboo, Wisconsin—from that, the International Crane Foundation was born.

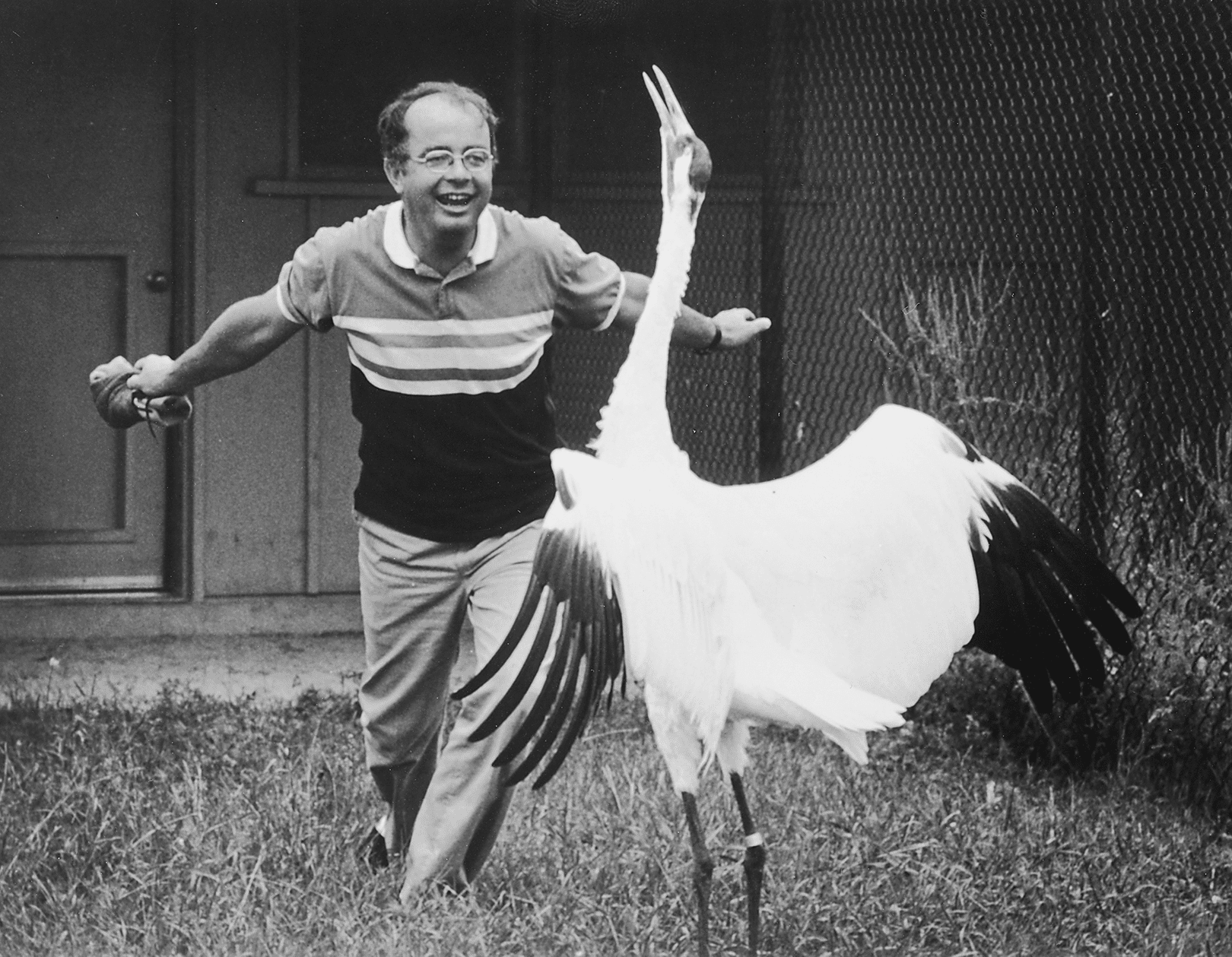

In the proceeding decades, Archibald and the crane foundation pioneered techniques in captive management and reintroduction of crane species, including the use of crane costumes, puppets, and courtship dance performances to induce successful reproduction in captive cranes. In the late 1970s, he famously spent three years acting as a male Whooping Crane to elicit a reproductive response from a female that had imprinted on humans. Archibald’s crane mating dance performances were such a phenomenon, they garnered him a spot on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in the 1980s.

Today, the International Crane Foundation houses aviaries containing all 15 of the world’s crane species (11 of which are still threatened) and receives 25,000 visitors a year—but its reach goes well beyond the work with captive birds. The foundation works in more than 50 countries to preserve habitat, educate communities, and advocate for policy changes in areas where cranes live. In addition to his continuing work with the International Crane Foundation, Archibald leads a World Conservation Union commission on crane survival.

When asked what achievement he was most proud of, Archibald reflected: “Thanks in part to the efforts of the International Crane Foundation, genetically viable populations of all species of cranes are maintained in captivity at many zoos and centers worldwide, nature reserves for all 11 threatened species have been established, and populations of the rarest cranes are slowly increasing. The achievements of the past half-century give me hope that at the end of the next half-century, all of the cranes will still bring their magic to landscapes worldwide.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library