Exploring the Falkland Islands

by Gary Kramer

July 15, 2010

cta slug=”lb-issue-nav-summer-10″]

To some people, the Falkland Islands are just a faraway place in the South Atlantic where Britain and Argentina fought a war in 1982. But long before those tragic events, the archipelago’s abundant wildlife was seen by Charles Darwin on his epic voyage on the HMS Beagle. During his visit in March 1833, the wildlife was abundant and exceedingly tame, yet he found the landscape somewhat drab and depressing. On my recent December visit, the wildlife was still approachable and abundant, and the scenery was spectacular. The number of bird species recorded in the Falklands increases every year with vagrants—mostly migrants blown in from the South American mainland. Currently, about 230 species have been recorded—70 breeding birds, 20 regular migrants, and more than 130 vagrants. The islands have two endemic species— the Falkland Steamerduck and the Cobb’s Wren.

You can visit the Falklands two ways—as a stopover point on a cruise ship bound for Antarctica or on a land-based trip. For birders and photographers, I highly recommend the land-based approach. All land tours begin and end with the once-a-week flight from Punta Arenas, Chile, to the Mt. Pleasant Airport near Stanley, the colorful capital of the islands. Each Saturday, a flight arrives dropping off passengers for a minimum one-week stay and taking others back to the mainland.

Upon arriving, I was met by Terrence McPhee, a fourth-generation islander and the owner of Kingsford Valley Farm in San Carlos. Although there are more than 400 treeless, windswept islands in the Falklands, the major islands are East and West Falklands. San Carlos is on East Falklands, along with Stanley and several essential points of interest.

Even before reaching San Carlos, we sighted some of the species I had traveled more than 7,000 miles from my home in California to observe. Upland (or Magellan) Geese were literally everywhere. After driving only a few miles from the airport, we saw a pair of Yellow-billed Teal in a roadside ditch and also glimpsed some Falkland Austral Thrushes and a spectacular red-breasted bird, the Long-tailed Meadowlark.

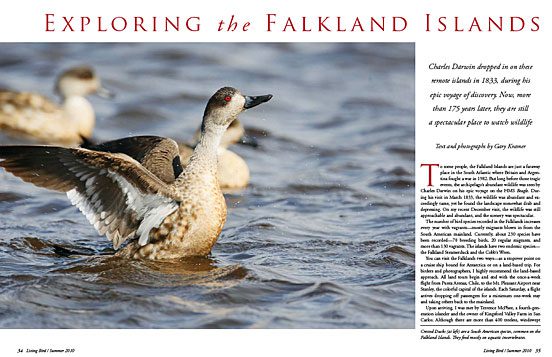

But it wasn’t until we reached San Carlos Bay that our sightings really kicked into high gear. A walk along the shoreline brought us face-to-face with one of the islands’ endemic birds— the unique Falkland Steamerduck. Although these large diving ducks cannot fl y, they flap their wings to help propel themselves across the surface of the water to escape danger or expel intruders from their territory. The splashing action reminded early observers of a paddle-wheel boat “steaming” across the water, hence their name.

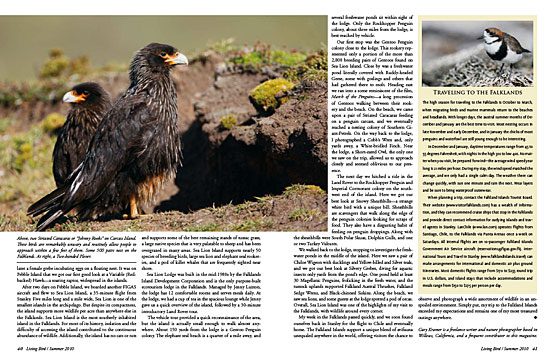

Not far from the steamerducks, we saw a pair of Kelp Geese. The male is all white, and the female is a barred brown and gray. Crested Ducks were feeding in the intertidal waters and Magellanic Oystercatchers foraged among the rocks. Later we traveled to the far side of San Carlos Bay and added Ruddy-headed Geese and both Magellan and Imperial cormorants to our species lists. Every bird was new and interesting.

One of the highlights of any visit to the Falklands is a trip to Volunteer Beach, a three-hour drive from Stanley or San Carlos over heath-covered landscape dominated by sheep farms. The road is part gravel, part dirt, and part bumpy jeep trail ending at a long sandy beach. Along the way, keep an eye out for small birds —Black-chinned Siskins, Dark-faced Ground-Tyrants, and White-bridled Finches.

Volunteer Point is home to the most northern colony of King Penguins in the world. Currently estimated at 500 pairs and increasing, the nesting colony is easily accessible. The noise of the penguins and the pungent aroma of guano nearly overwhelm your senses. King Penguins can be found in their rookeries year round, so birds are present every month of the year with chicks in various stages of development. We saw adults incubating eggs and young ready to fledge. Between the King Penguin colony and the beach are a number of Magellanic Penguins, which have a loud, braying call, remarkably similar to the sound of a donkey. Unlike King Penguins, which nest in tight colonies, Magellanic Penguins are burrow nesters.

Only a few hundred yards from the King Penguins was a colony of Gentoo Penguins, most of which were incubating or with young. We sat on the periphery of the colony and watched as adults returned from the sea. Upon arriving at their nests, mated pairs greeted one another by calling and pointing their beaks skyward. The advancing penguin would walk into position to replace its mate, careful not to step on the young chicks. Almost instantly, the chicks started begging for food. We were so close we could see squid being regurgitated for the chicks.

For visitors with limited time in the Stanley area, there are two good birding sites close to town. Gypsy Cove is a 15-minute drive from Stanley and supports several hundred pairs of Magellanic Penguins, both Imperial and Magellan cormorants, and one of the few birds found in both North America and the Falklands—the Black-crowned Night-Heron. A bit farther afield, Bluff Cove Lagoon is still less than an hour’s drive from Stanley. This site supports a colony of about 2,000 Gentoo Penguins and a dozen or so King Penguins. The larger Kings look like bouncers at a nightclub, standing tall on the edge of the colony. Ruddy-headed and Upland geese graze nearby, and Dolphin Gulls and Turkey Vultures fl y overhead.

A few hundred yards away is a sandy beach frequented by Southern Giant-Petrels—large, drab, brown seabirds often seen soaring over the surf line. Along the beach, look for attractive Rufous-chested Dotterels, tiny Two-banded Plovers, Magellanic Oystercatchers, and White-rumped Sandpipers, the latter migrating all the way from Canada. After visiting the penguin rookery and the beach, drop into the Sea Cabbage Cafe for hot tea or coffee and home-baked cakes and pastries.

Our next stop was Carcass Island, a 5,000-acre sheep farm that takes its name from HMS Carcass, a ship that visited the island in the late 1800s. Owned by Rob and Lorraine McGill for more than 30 years, the island is free of cats and rats and therefore a haven for passerines along with waterfowl, penguins, and shorebirds. Carcass is reached by a one-hour flight from Stanley on a 10-passenger Islander aircraft operated by the Falkland Islands Government Air Service (FIGAS). Here visitors are housed in the sheep-station headquarters in comfortable double-occupancy rooms, each with a bath on a full-board basis.

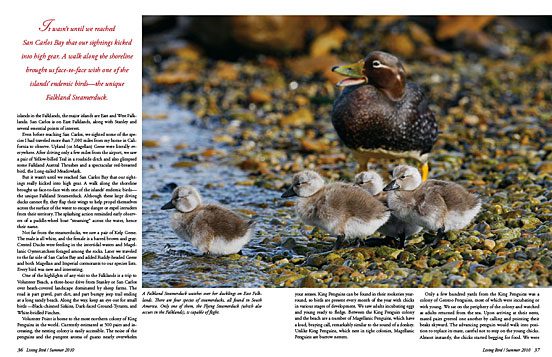

Less than 100 yards from the house is a rocky beach backed by headlands. Along the beach, we found Ruddy-headed and Kelp geese with young goslings, Crested Ducks and Falkland Steamerducks with ducklings, and both Magellanic and Blackish oystercatchers with downy young. About a mile from the headquarters, a rocky pinnacle just offshore was the site of a Striated Caracara nest with three nestlings. Known locally as the “Johnny Rook,” this raptor is relatively rare, inhabiting remote parts of South America. The Falklands support about 500 breeding pairs—approximately 75 percent of the world population of the species. Tame and fearless, the adults were curious, and sometimes landed only a few yards from us.

On the way back from the caracara nest, we followed a trail through the grass-covered uplands and came upon a singing Cobb’s Wren and later a Falkland Sedge Wren. Blackish Cinclodes were abundant along with Falkland Austral Thrush, Falkland Pipit, White-bridled Finch, and a pair of South American (Magellanic) Snipe, which decided to freeze rather than fly, offering close-up photographic opportunities.

The next morning, Rob McGill drove us across the island to “The Plains”—an area of grasslands, freshwater ponds, and beaches. Southern elephant seals lay hauled out on the beach, and the ponds were filled with waterfowl, including a large molting flock of Falkland Steamerducks along with Crested Ducks, Silver Teal, and Ruddy-headed and Upland geese. On the beach was a large nesting colony of Kelp Gulls and a smaller nesting colony of crimson-legged Dolphin Gulls. Oystercatchers were abundant and Kelp Geese with young seemed to be around every bend.

After two days on Carcass Island, we boarded another FIGAS aircraft and flew to Pebble Island. Nineteen miles long and about four miles wide, Pebble is the third-largest offshore island in the archipelago. Here visitors stay at Pebble Island Lodge, formerly the farm manager’s house, now offering six comfortable rooms and daily meals.

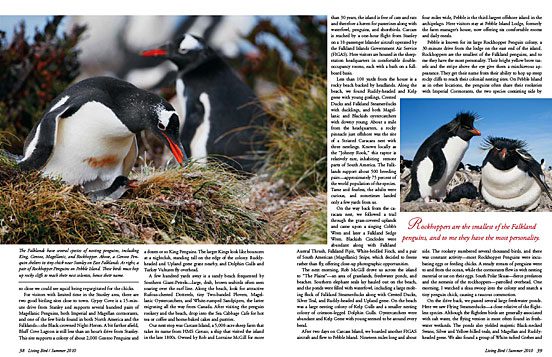

Pebble is known for its large Rockhopper Penguin colony, a 30-minute drive from the lodge on the east end of the island. Rockhoppers are the smallest of the Falkland penguins, and to me they have the most personality. Their bright yellow brow tassels and the stripe above the eye give them a mischievous appearance. They get their name from their ability to hop up steep rocky cliffs to reach their colonial nesting sites. On Pebble Island as in other locations, the penguins often share their rookeries with Imperial Cormorants, the two species coexisting side by side. The rookery numbered several thousand birds, and there was constant activity—most Rockhopper Penguins were incubating eggs or feeding chicks. A steady stream of penguins went to and from the ocean, while the cormorants flew in with nesting material or sat on their eggs. South Polar Skuas—fierce predators and the nemesis of the rockhoppers—patrolled overhead. One morning, I watched a skua swoop into the colony and snatch a tiny penguin chick, causing a raucous commotion.

On the drive back, we passed several large freshwater ponds. Here we saw Flying Steamerducks—a close relative of the flightless species. Although the flightless birds are generally associated with salt water, the flying version is most often found in freshwater wetlands. The ponds also yielded majestic Black-necked Swans, Silver and Yellow-billed teals, and Magellan and Ruddyheaded geese. We also found a group of White-tufted Grebes and later a female grebe incubating eggs on a floating nest. It was on Pebble Island that we got our first good look at a Variable (Red-backed) Hawk—a soaring raptor, widespread in the islands.

After two days on Pebble Island, we boarded another FIGAS aircraft and flew to Sea Lion Island, a 35-minute flight from Stanley. Five miles long and a mile wide, Sea Lion is one of the smallest islands in the archipelago. But despite its compactness, the island supports more wildlife per acre than anywhere else in the Falklands. Sea Lion Island is the most southerly inhabited island in the Falklands. For most of its history, isolation and the difficulty of accessing the island contributed to the continuous abundance of wildlife. Additionally, the island has no cats or rats and supports some of the best remaining stands of tussac grass, a large native species that is very palatable to sheep and has been overgrazed in many areas. Sea Lion Island supports nearly 50 species of breeding birds, large sea lion and elephant seal rookeries, and a pod of killer whales that are frequently sighted near shore.

Sea Lion Lodge was built in the mid-1980s by the Falklands Island Development Corporation and is the only purpose-built ecotourism lodge in the Falklands. Managed by Jenny Luxton, the lodge has 12 comfortable rooms and serves meals daily. At the lodge, we had a cup of tea in the spacious lounge while Jenny gave us a quick overview of the island, followed by a 30-minute introductory Land Rover tour.

The vehicle tour provided a quick reconnaissance of the area, but the island is actually small enough to walk almost anywhere. About 150 yards from the lodge is a Gentoo Penguin colony. The elephant seal beach is a quarter of a mile away, and several freshwater ponds sit within sight of the lodge. Only the Rockhopper Penguin colony, about three miles from the lodge, is best reached by vehicle.

Our first stop was the Gentoo Penguin colony close to the lodge. This rookery represented only a portion of the more than 2,800 breeding pairs of Gentoos found on Sea Lion Island. Close by was a freshwater pond literally covered with Ruddy-headed Geese, some with goslings and others that had gathered there to molt. Heading east we ran into a scene reminiscent of the film, March of the Penguins—a long procession of Gentoos walking between their rookery and the beach. On the beach, we came upon a pair of Striated Caracaras feeding on a penguin carcass, and we eventually reached a nesting colony of Southern Giant- Petrels. On the way back to the lodge, I photographed a Cobb’s Wren and, only yards away, a White-bridled Finch. Near the lodge, a Short-eared Owl, the only one we saw on the trip, allowed us to approach closely and seemed oblivious to our presence.

The next day we hitched a ride in the Land Rover to the Rockhopper Penguin and Imperial Cormorant colony on the southwest end of the island. Here we got our best look at Snowy Sheathbills—a strange white bird with a unique bill. Sheathbills are scavengers that walk along the edge of the penguin colonies looking for scraps of food. They also have a disgusting habit of feeding on penguin droppings. Along with the sheathbills were South Polar Skuas, Dolphin Gulls, and one or two Turkey Vultures.

We walked back to the lodge, stopping to investigate the freshwater ponds in the middle of the island. Here we saw a pair of Chiloe Wigeon with ducklings and Yellow-billed and Silver teals, and we got our best look at Silvery Grebes, diving for aquatic insects only yards from the pond’s edge. One pond held at least 30 Magellanic Penguins, frolicking in the fresh water, and the tussock uplands supported Falkland Austral Thrushes, Falkland Sedge Wrens, and Black-chinned Siskins. Along the beach, we saw sea lions, and some guests at the lodge spotted a pod of orcas. Overall, Sea Lion Island was one of the highlights of my visit to the Falklands, with wildlife around every corner. My week in the Falklands passed quickly, and we soon found ourselves back in Stanley for the flight to Chile and eventually home. The Falkland Islands support a unique blend of avifauna unequaled anywhere in the world, offering visitors the chance to observe and photograph a wide assortment of wildlife in an unspoiled environment. Simply put, my trip to the Falkland Islands exceeded my expectations and remains one of my most treasured outings anywhere.

Gary Kramer is a freelance writer and nature photographer based in Willows, California, and a frequent contributor to this magazine. Visit his website:http://www.garykramer.net

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library

Don't miss a thing! Join our email list

The Cornell Lab will send you updates about birds,

birding, and opportunities to help bird conservation.