Evidence Of Absence: Northern Spotted Owls Are Still Vanishing From The Northwest

April 12, 2016You won’t meet a Northern Spotted Owl in this story.

The first reason is that, by the time I drive west from Sutherlin, Oregon, with Janice Reid one sunny November morning, the raptor’s breeding season is over. Spotted Owls are territorial while they nest and can be summoned with a hoot simulating an intruder. But once their owlets are grown, the birds melt like ghosts into the forest.

The second reason is grimmer: Spotted Owls are becoming much harder to find.

Reid, a small woman with wavy silver hair, is the U.S. Forest Service’s project director on the 400 square-mile Tyee study area, one of 11 such study sites in western Washington, Oregon, and northern California involved in a decades-long effort to track Spotted Owl population trends.

“I essentially live in this truck in summer, so it’s still got dust and fir needles from field work,” she apologizes, explaining that the dog smell is from a Labrador retriever she’s trained to track owl pellets. She’s studied Spotted Owls in these mountains since 1985, lured by their docile personalities and the puzzle of locating them in the tangled woods.

“You can see your reflection in their eyes sometimes, you get so close,” she says. “And they have big brown eyes. Maybe it’s just human nature to like big brown eyes.”

Past a gate guarding access to the Tyee’s checkerboard of private and U.S. Bureau of Land Management forest, Reid parks and steps onto a coin-scatter of gold leaves. Trees of all sizes clog the slope above us—centuries-old Douglas-fir, feather-plumed cedar, spindly vine maple.

This BLM stand is good Spotted Owl habitat, Reid explains, despite adjacent clearcuts. The ancient trees offer nesting cavities, and the layered foliage provides cover from predators and summer heat, while downed logs harbor prey. Perhaps for these reasons, this has been one of the Tyee’s most prolific nest sites. Successive Spotted Owl pairs here fledged more than 20 owlets in 20 years—three times the study area’s average. Then, in 2014, the last pair vanished.

“We don’t know where they are,” Reid says. “We don’t know if they’re dead, or just floating around the landscape.”

Twenty-six years after the Northern Spotted Owl was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, disappearances like these are a common story. By 1990, wholesale cutting of old-growth trees had sent the owls and other wildlife such as Marbled Murrelets and salmon into a tailspin, spurring a bitter fight between environmentalists and logging interests over the fate of northwestern forests. A 1994 agreement called the Northwest Forest Plan—which stepped up habitat protections for the owls and other species across more than 24 million acres of national forest, BLM, and other federal lands—was supposed to fix all that. By some environmental measures, it’s working: old-growth logging all but halted on federal land and some watersheds improved. For a while, Northern Spotted Owls seemed headed toward stability, too. The average annual rate of range-wide decline improved from 3.9 percent in 1998 to 2.9 percent in 2008.

Masked beneath those figures, however, was a growing threat: An exploding population of invasive Barred Owls was moving in, shoving Spotted Owls from territories like this one. Today, the rate of Northern Spotted Owl decline is back up to 3.8 percent.

Given Barred Owls’ role in the Spotted Owls’ steepening slide, some timber companies and rural governments have called for rollbacks of forest protections. But safeguarding habitat may be more important than ever.

Protecting Old Growth Forests

“The bottom line is that extinction rates went down when the amount of habitat went up,” U.S. Geological Survey biologist Katie Dugger, lead author of the 2015 demographic study, said in a presentation on the findings last fall. “Spotted Owls cannot exist without old-growth forest. And now we’re talking about two species trying to use the same space, so in fact we need more of it.”

These birds are disappearing from across their range. It’s such a good feeling when you find that they’re still there. Forests like these once stretched from British Columbia to Northern California, but many owls are now confined to these small isolated patches of mature forest that remain after a century and a half of intensive logging. Pairs like this will mate for life and may live 20 years.

They’re primarily nocturnal, but will hunt by day when the opportunity arises and they have a hungry chick to feed. Spotted owls are perch and pounce predators with remarkable eyesight and facial disks that amplify their hearing and enable them to pinpoint prey in total darkness. They quietly wait and then swoop down to snag unsuspecting prey with their talons.

This pair did well raising a chick to fledging age in 2015, but the isolation of many of these pairs in these small patches of forest have made them much more susceptible to starvation and to predation and to failed breeding. And once chicks like this one leave the nest, it is very difficult for them to find a territory of their own.

End of Transcript

Now the Forest Service and BLM are moving to update the land-use plans that fall under the Northwest Forest Plan, and new battle lines are being drawn over where and how additional habitat protections should be placed. It is, in a way, a quieter, more bureaucratic reprise of the old timber wars, only with a more complicated mix of threats and an even more precarious future for Spotted Owls.

“Spotted Owls cannot exist without old-growth forest.”

—Katie Dugger, USGS

The outcome matters even if the species is ultimately wiped out in the Northwest. After all, the fight “was never really just about Spotted Owls,” points out Eric Forsman, who, until retiring in 2015, was one of the Forest Service’s top Spotted Owl biologists. “It was always more about protecting the incredible structural and species diversity that was present in these older forests.”

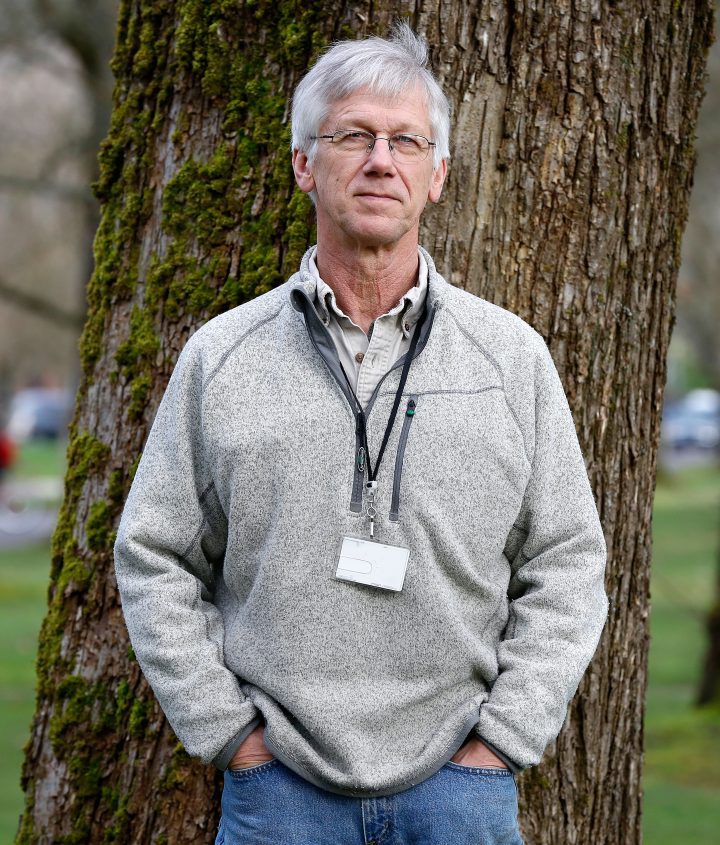

A few days before Thanksgiving, I meet Forsman at the Forestry Sciences Laboratory on the Oregon State University campus. He leads me through a warren of hallways to a windowless room crammed with office furniture.

“I’m the only one who’s ever here,” he comments, pointing at one dusty workstation. “That guy might be dead.”

Forsman has square shoulders and a certain appraising merriment. Nine binders on his desk are devoted to ropes and rigging—material for a class he’s teaching on tree climbing for wildlife research. Another is labeled simply “VOLE TEETH.” Suspenders hung from Forsman’s cubicle wall are emblazoned with “SPOTTED OWL HUNTER” in red letters—a souvenir from a time when tensions were so high that some owls turned up dead.

Metaphorically speaking, the slogan could apply to Forsman, too. He started stalking Spotted Owls in the early 1970s, after a face-to-face encounter inspired a master’s degree project searching for the species across Oregon. At that time, very little was known about its basic biology. Ominously, he found logging had occurred or was scheduled in more than half of the owl habitats he located. Driven by a thriving export market in the ‘70s and ‘80s, federal timber harvests in Washington, Oregon, and northern California rocketed to 4 to 5 billion board feet annually—rates that would have eliminated federal Spotted Owl habitat outside parks and wilderness in decades. Forsman and other scientists raised the alarm.

Environmental groups soon piled on. The Seattle Audubon Society sued the Forest Service for failing to meet its National Forest Management Act obligation to maintain “viable” populations of species, and in 1989 won an injunction from federal district judge William Dwyer blocking over 100 timber sales. Two years later, Dwyer blocked further logging in owl habitat until the feds came up with defensible protections.

The Northwest Forest Plan—forced by the Clinton Administration and developed by scientists in just 90 days—was the compromise that ended the stalemate. On both national forest and BLM land, it created 10 million acres of new reserves to safeguard old-growth forests and stream corridors from further cutting (though some of the land inside reserves had already been clearcut). Another 5.5 million acres were to provide regular timber harvests, with a predicted annual output of about 1 billion board feet. Because about 20 percent of remaining ancient stands were not inside reserves, the agreement also instated a “Survey and Manage” mitigation program that required agencies to look for a suite of rare species before logging could occur, and protect them with buffers when found.

At the time, Barred Owls were still a novelty in the Northwest. It’s impossible to know for sure what facilitated their arrival, but the prevailing theory is that the Great Plains once served as a vast moat, confining them to their native eastern forests. As westbound settlers planted trees and snuffed out fires, new forest crept along the Missouri River and its tributaries. Barred Owls leapfrogged into Washington in 1965, Oregon in 1972, and California in 1976.

Not even the Northwest Forest Plan—a revolutionary advancement of landscape-scale ecosystem management—was sweeping enough to deal with a continent in flux. Worse, it had come too late to reverse the decline that would make Spotted Owls so vulnerable to the new arrivals.

Threatened by Barred Owls

As Barred Owls have expanded across the Pacific Northwest, they’ve settled everywhere—from suburban neighborhoods to the same old-growth forests beloved by Spotted Owls. Because they’re generalist predators, they can pack in much tighter: in Oregon’s Coast Range, researchers recently found Barred Owls three to four pairs deep in territories that once supported one Spotted Owl pair. Add the fact that Barred Owls can produce four times as many owlets as Spotted Owls, and the math is bleak.

“It makes me sad,” says Forsman, who’s pessimistic about the Spotted Owls’ prospects. But “range expansions are a part of natural systems. We just happened to be watching when one occurred. Even if [we’re to blame], we’re probably going to have to live with it.”

In Washington’s Olympic National Park, Barred Owls have filled the drainages like water in a bathtub. Last year, the monitoring crew there found just three Spotted Owl pairs and three single birds on 54 territories.

“We’re essentially proving absence on 80 percent of the sites,” says National Park Service wildlife biologist Scott Gremel. “It’s impossible for me to see a pathway where we don’t have extirpation of Spotted Owls from the Olympic Mountains unless we go to Barred Owl management.”

“You hear that?” whispers David Wiens. He fiddles with a remote control and a male Barred Owl caterwaul—a cackle not unlike that of a circus clown who’s huffed helium—pours through the fog from a speaker at our feet. A moment later, a fluting sound rolls back up the forested drainage. It’s a female Barred Owl. She calls again, nearer now. Suddenly, a whitish shape arrows from the bushes high into a Douglas-fir. I can’t distinguish her silhouette from the foliage until her head swivels in that owlish, Linda Blair way.

Had she landed closer, we would be able to see just how alike and how different she is from a Spotted Owl: similar size, but larger; similar brown coloring, but lighter, with streaks down her breast instead of spots. Barred and Spotted owls belong to the same genus and occasionally interbreed. And though Wiens admires the Barred Owl’s versatility and intelligence, if circumstances were slightly different, he might shoot her with a 12-gauge shotgun.

Wiens, a USGS biologist, and Katie Dugger are leading a federal Barred Owl removal experiment launched in 2013. Dressed in a navy raincoat with a beanie propped behind his ears, Wiens’ lean face has a heaviness that suggests the tremendous difficulty of his job. Over the next few years, field crews under his supervision will kill around 1,700 Barred Owls in four study areas scattered across the Northern Spotted Owl’s range—including this one, in Oregon’s Coast Range.

“It’s impossible for me to see a pathway where we don’t have extirpation of Spotted Owls from the Olympic Mountains unless we go to Barred Owl management.”

—Scott Gremel, National Park Service biologist

“I’ve studied raptors my whole career,” Wiens says. “I never imagined I’d end up doing anything like this.”

Even so, he recognizes the need. Where past studies have relied on correlations, this experiment will provide definitive answers about how Barred Owls are affecting their dwindling cousins—and, potentially, entire ecosystems.

“It’s important to know what those impacts are before, 10 years from now, we have quiet forests because this invasive predator cleaned everything out,” Wiens says.

The decision to make the experiment deadly wasn’t easy. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service studied multiple approaches and tapped a bioethicist and more than 40 stakeholders to navigate the treacherous moral ground involved. In the end, the nonlethal options didn’t appear feasible or humane. Translocating Barred Owls would exacerbate the Spotted Owls’ dilemma elsewhere and might still kill Barred Owls. Storing them in prolonged captivity would make it impossible to return them to the wild, and only a few zoos and raptor centers expressed interest in providing permanent homes.

The animal advocacy groups Friends of Animals and Predator Defense have sued, arguing that the approach violates the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. But otherwise, the experiment—calibrated to ensure a quick kill, affecting a tiny fraction of the Pacific Northwest Barred Owl population, and carried out only when pairs aren’t raising young—appears to have garnered broad, if uncomfortable, backing.

“We really wrestled with the ethics of controlling one species to benefit another, but there was only one alternative we thought was scientifically credible enough to go ahead and conditionally support,” says Chris Karrenberg, Seattle Audubon’s former Conservation Committee chair. “Still, to support landscape-style management of Barred Owls is a different issue.”

Results from a five-year study in northern California on timberlands belonging to the Green Diamond Resource Company are promising. Lead investigator Lowell Diller found that, within days of Barred Owl removal, Spotted Owl pairs he hadn’t seen in years reappeared on historic nest sites. According to Dugger’s demographics study incorporating his data, Green Diamond’s treatment areas are the only place where Northern Spotted Owl population trends look positive, growing by an estimated 3 percent annually.

Similar findings in the larger federal experiment, however, would raise thorny management questions.

“We would have to do it forever and on fairly large areas to actually have an effect,” points out Forsman. “And that’s just not going to happen.”

Only after the experiment is done will the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service make a decision about whether to undertake that approach, says the agency’s removal project coleader, Robin Bown: “In the end, we may choose not to do anything. But this way, we’ll know how effective removal is. And how costly.”

Diller says even temporary relief from Barred Owls could have benefits: “Every decade that we buy for Spotted Owls increases the chance that they will adapt to this new threat and buys time for us to look for more palatable management options.”

For coexistence to be possible, preserving remaining habitat may now be more important than ever. Wiens says further forest fragmentation in the face of the Barred Owl onslaught will only hasten the Spotted Owl’s decline: “The long-term issue continues to be habitat loss. The more loss there is, the greater the competitive pressure becomes.”

And it appears that the vast networks of habitat set aside in the 1990s aren’t enough.

The Northwest Forest Plan

The Northwest Forest Plan was always a long game. Its creators anticipated it would be several decades before reserve forests grew back enough to begin offsetting ongoing habitat loss from logging and wildfire elsewhere. As new threats became evident, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2011 recommended extending protections to more forest and as many occupied Spotted Owl territories as possible. A year later, it designated 9.6 million acres as “critical habitat” necessary for the species’ recovery, which can open the door to additional land-use restrictions. Although much of that fell inside existing reserves, it also included forest that had been open for logging.

That hit a sore spot: lands under the Northwest Forest Plan have produced significantly less lumber than predicted, thanks to lawsuits and regulations that prevented clearcuts, as well as low Congressional appropriations and the vagaries of the timber market.

“The industry took a major hit to protect the Northern Spotted Owl. And as it turns out, it didn’t work,” says Travis Joseph, president of the American Forest Resources Council, a regional trade association. “Now, to protect this species from a natural threat, we have to set more land aside? It makes folks angry.”

For their part, environmentalists worry that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service isn’t being protective enough. For example, its 2011 Northern Spotted Owl recovery plan emphasizes forest thinning to insulate owl habitat against wildfire. But Dominick DellaSala, chief scientist at the nonprofit Geos Institute and former member of federal Spotted Owl Recovery Team, says thinning may cause near-term harm to Spotted Owls by reducing prey and destroying more habitat than it saves. The species, DellaSala says, “is actually quite resilient to forest fires.”

“The industry took a major hit to protect the Northern Spotted Owl. And as it turns out, it didn’t work.”

—Travis Joseph, American Forest Resources Council

Earlier this year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service authorized a post-fire salvage logging project in the Klamath National Forest in northern California that will cause the incidental take, or death, of 37 nesting pairs of Spotted Owls. The American Bird Conservancy strenuously urged federal agencies to reconsider and be more cautious with projects in Spotted Owl habitat.

Meanwhile, as the U.S. Forest Service and BLM update the land-use plans that fall under the Northwest Forest Plan, nobody seems happy. The 1994 version featured tight coordination between the two agencies, but this time BLM is developing its own plan. Most of its draft proposals make the protected reserves bigger, raising the ire of timber companies and affected counties. BLM also proposes to ramp up clearcutting elsewhere, eliminate the Survey and Manage program, and shrink forest buffers along waterways, thus riling environmentalists.

BLM project manager Mark Brown says his agency is obligated to provide a sustained timber yield from its lands in western Oregon. So it’s trying to minimize conflicts through a sort of zoning. The larger reserve network captures virtually all of the old growth, which in theory negates the need for Survey and Manage and frees up timber harvest areas to provide more reliable sales.

That doesn’t assuage environmentalists’ concerns: “Expansion of the reserve system is a net positive,” says Doug Heiken, conservation and restoration coordinator at Oregon Wild. But loopholes may undermine those protections, he says, and they “don’t justify elimination of stream protections and Survey and Manage while forests in reserves are still recovering from decades of overcutting.”

The BLM anticipates that its final plan will be out in April 2016. The Forest Service recently completed a series of listening sessions and is now compiling a scientific review of the Northwest Forest Plan, with the aim of beginning revisions by early 2018.

As the battle over federal lands heats up, it’s unclear whether state and private forests will play an expanded role in Spotted Owl recovery. Little habitat is left there—the Northwest Forest Plan, with its federal lands focus, had the side-effect of increasing the intensity of logging on state and private lands, where the rules are weaker and the Endangered Species Act holds far less sway. There are some incentive-based programs enlisting private landowners in California and Washington to manage for owls, but in Oregon there’s been virtually no buy-in.

Some conservation groups such as Seattle Audubon have lobbied to change the Spotted Owl’s federal listing status from “threatened” to “endangered” to afford the owls more protection. That change, currently being considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, would increase the scrutiny of projects that impact owls on federal land or require federal permits. But agency Northern Spotted Owl specialist Betsy Glenn says that it won’t alter actual species management on the ground very much.

What does the future hold?

Back on the Tyee, Janice Reid pulls the truck onto a hilltop and points out the severe demarcation of a section line between thickly forested BLM land and logged private land—a pattern that repeats across the ridgelines to the horizon. That clearcut used to have a nest tree, she tells me. Oregon forestry rules allowed it to be cut down because Spotted Owls hadn’t used it in 10 years. Before chainsaws tore through, Reid found a Barred Owl pair in the spot.

“If you haven’t seen a Spotted Owl in the wild, I suggest you go out and do so.”

—Katie Dugger, USGS

“Now they’re gonna find some other Spotted Owl site to occupy,” she says, “and push another Spotted Owl pair out.”

Reid is silent as we return to the upper bound of the BLM grove where we began our day. After we park, I follow her down the moss-covered slope, ducking branches until the forest opens into a trunk-pillared atrium. She calls back to me that she’s found one of the nest trees—a Douglas-fir. A metal tag marks the year Spotted Owls made it their home: 2004. Twenty yards farther, another reads 1991. Under the circumstances, they have a dark finality, like the dates on headstones.

“I used to be able to walk in here and not do any hooting and I’d just look up and spot ‘em,” Reid says, craning her neck, as if what we’ve been searching for might suddenly appear. “I haven’t given up hope.”

Still, she adds, maybe it’s like the USGS’s Katie Dugger said in her presentation: “If you haven’t seen a Spotted Owl in the wild, I suggest you go out and do so.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library