Analysis: Do Bird Feeders Help or Hurt Birds?

By Emma Greig

January 11, 2017

From the Winter 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Consider these facts:- According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, more than 50 million North Americans feed birds. That’s more than 1 million tons of seed, what scientists call supplementary feeding, provided to birds every year.

- According to the most recent State of North America’s Birds report, one-third of all our continent’s bird species need urgent conservation action. More than 400 birds are on the report’s Watch List of species considered most at risk of extinction.

There are some natural questions that emerge from these facts: Is this massive annual experiment in supplementary feeding affecting our continent’s bird populations? And if so, is feeding birds harmful, or helpful?

There are some clear benefits of feeding birds. We know that some regular feeder visitors, such as Northern Cardinals, are doing very well, because their populations are growing and ranges expanding. But supplementary feeding has also been associated with negative impacts such as disease transmission, deaths from window strikes (when birds fly away from a feeder and into a house), and increased predation pressures (such as Cooper’s Hawks feeding themselves by feasting on feeder birds). Can we reconcile these disparate consequences of bird feeding and determine if feeding is actually harmful on a broad scale?

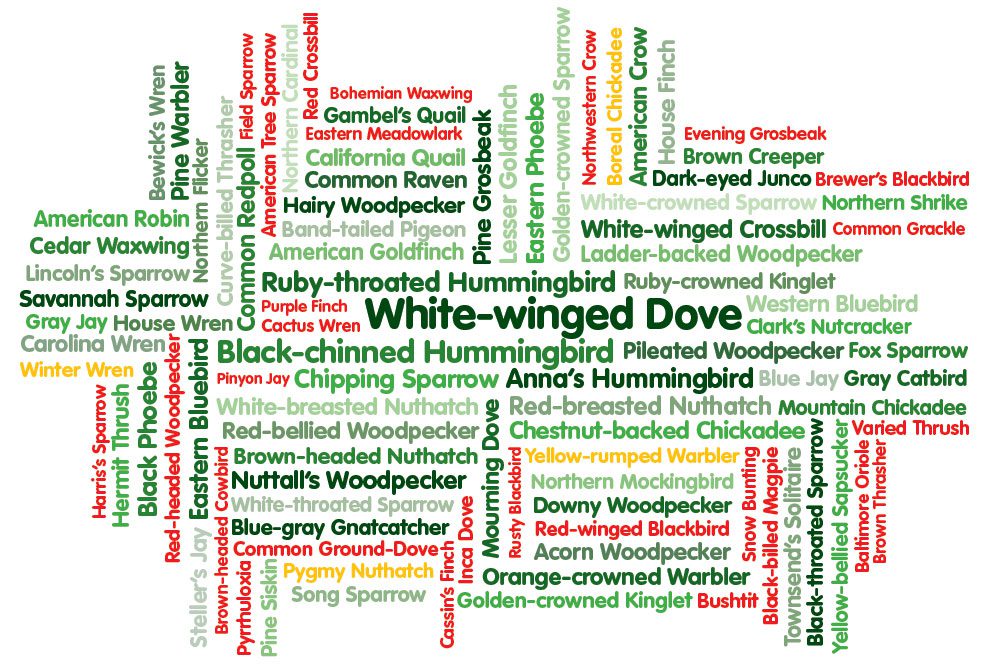

We decided to put the nearly 30 years of Project FeederWatch data to use to try to answer this question. We made one simple prediction: if feeding birds is harmful, then the species that use feeders the most should be doing the worst, all else being equal. FeederWatch data would tell us how often a species used feeders, and Christmas Bird Count data would give us an independent estimate of how each species was doing over time. We looked at 98 species that use feeders at least a moderate amount and excluded species that rarely visit feeders, because lumping these species would be as logical as comparing chickadees to herons.

We found that species that use bird feeders the most tended to be doing just as well as, or better than, species that use feeders more sporadically. For example, Red-bellied Woodpeckers visit feeders regularly and are thriving, whereas Pinyon Jays visit feeders more sporadically and are showing declines. The feeder species that showed declines seem to be faced with non-feeder–related pressures, such as habitat loss. For Pinyon Jays, the most pressing problem is the destruction of pinyon pine habitat. We are still working to refine this analysis, but the take-home message so far is that species that visit bird feeders a lot tend to be doing very well.

But which are the species in need of urgent conservation action, according to the State of the Birds report? Well, they aren’t visiting your feeders. The species most in trouble are seabirds, shorebirds, and tropical forest dwellers. This means that although feeding birds may not be harmful to the species that use feeders the most, it also isn’t helpful to the species that most need our help.

But don’t take down your feeders in despair. One of the most important impacts of feeding birds is that it allows people to feel connected to the natural world. One FeederWatch participant sent out a homemade holiday card with a photograph of a Black-capped Chickadee on a miniature sleigh full of sunflower seeds. The message on the card read: “Feeding the birds is the best present you could give them.” The photograph illustrates the joy that feeding birds can bring right to our homes. That joy and connection are not trivial. On the contrary, it can inspire people to engage in environmental advocacy and conservation action to help the many species that need more than sunflower seeds.

We still have a lot to learn about the impacts of feeding birds, such as possible indirect effects on migratory species, or possible effects on generalist predators that may subsequently impact populations of non-feeder birds. Nonetheless, this work is a start, and gives us a new perspective on this tremendously popular activity. Is feeding birds the best gift you can give them? Maybe not, but it might be the best gift we can give ourselves.

Emma Greig leads Project FeederWatch. This essay summarizes research conducted by Greig and Cornell Lab Citizen Science Director David Bonter and presented at the 2016 North American Ornithological Conference.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library