Add Flair to Your Life List By Tracking Down Evolution’s Most Distinctive Birds

By Eliot Miller

September 19, 2018

From the Autumn 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Do you keep a life list—a list of birds you’ve seen over the course of your life? What about a county list? Or a year list? Or a list of birds you’ve seen out your office window, or on your birthday?

Many birders keep these types of lists. The common currency in most is the species: one species equals one entry on the list. It’s very egalitarian. But to an evolutionary biologist (like me), not all birds are equal.

Evolution offers a different form of currency for valuing bird species. For example, the Magpie Goose of Australia is only distantly related to any other modern bird species. Fossil evidence demonstrates that other species in its family went extinct 20 or 40 million years ago. That makes the Magpie Goose a living fossil, gracing us with fantastic traits from avian ages of the past—feet that, unlike those of other geese, are only partially webbed, and an elaborate, elongated trachea for broadcasting their honking vocalizations. This is not your average goose; surely it deserves some distinction on a life list for being the only currently living species of its genus and family.

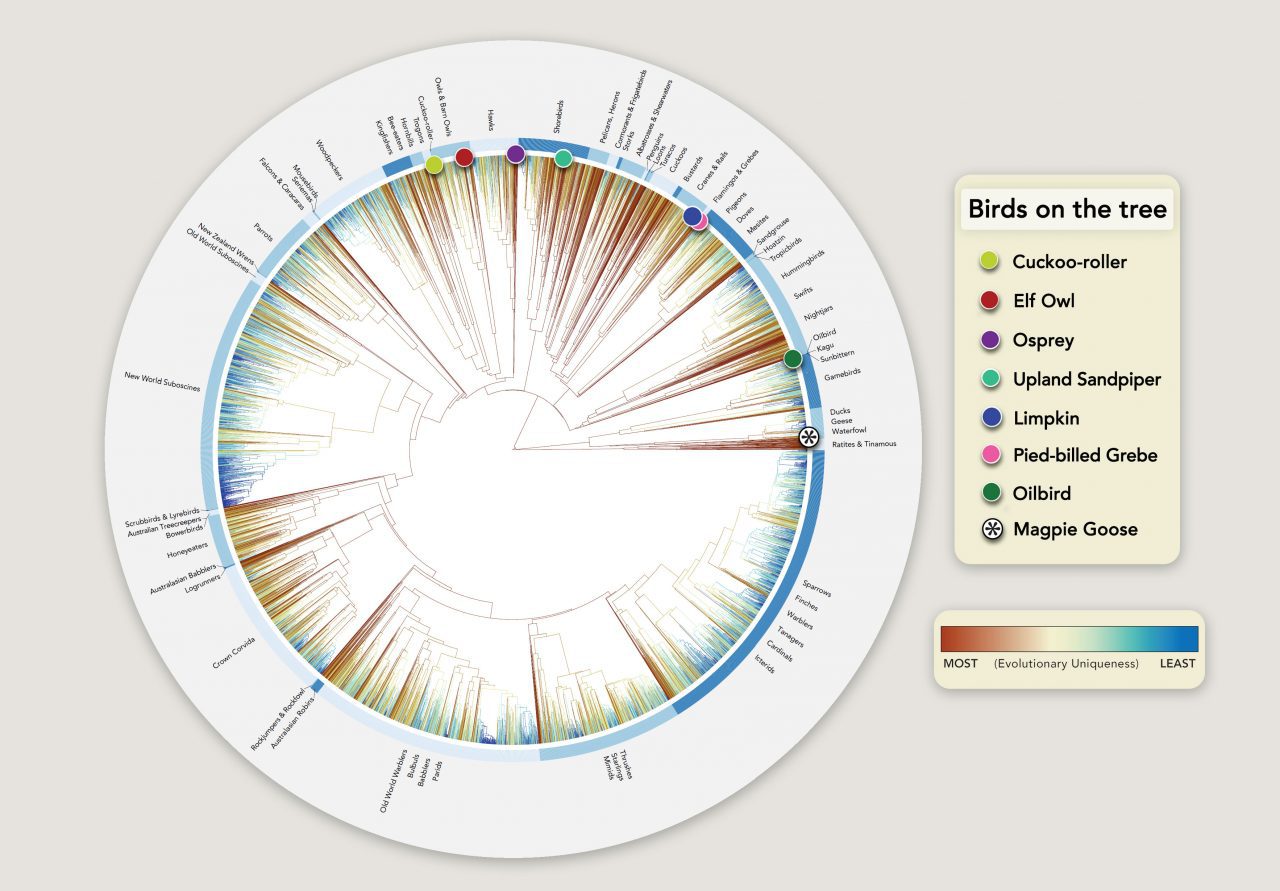

There are a variety of ways to measure the evolutionary uniqueness of a species. The most informative of these measures involve the use of a phylogenetic tree —a depiction of the evolutionary relationships among a set of species. Looking at the phylogeny of all the world’s bird species provides a different perspective on some of the world’s most unique birds.

Some birds stick out of the avian phylogenetic tree, demanding your attention. They are the one-offs, the austere branches where a single bird species is the only representative of its evolutionary lineage.

On a Phylogenetic Tree, the Most Distinctive Birds Sit on the Long Branches

If you see one of these special birds, maybe add a star or an asterisk next to its name on your life list. For you’ve seen a species unlike many others on the planet today, a bird that has followed its own evolutionary trajectory for millions of years. There are many such birds (look for them on the red branches of the illustration above). Here’s a short list of some of our favorites:

-

-

Magpie Goose

(Anseranas semipalmata)

The Magpie Goose of Australia is spectacularly distinct; its closest relatives went extinct 20 to 40 million years ago. This living fossil graces us with fantastic traits from avian ages of the past—feet that are only partially webbed, an elaborate, elongated trachea that turns its voice into a honker of a wind instrument, and more. -

Cuckoo-roller by Nigel Voaden/Macaulay Library. Cuckoo-roller

(Leptosomus discolor)

Cuckoo-rollers are endemic to Madagascar and nearby islands off the east coast of Africa. They are so unique they are assigned their own taxonomic order, a rank above the level of family. These birds are so rarely studied that their evolutionary relationships to other birds are unclear, and scientists are not even entirely sure what they eat. The Cuckoo-roller’s island-restricted distribution is a good example of the way large islands act as museums, allowing the long-term persistence of evolutionarily unique lineages (like the Magpie Goose). -

Oilbird by Luke Seitz/Macaulay Library. Oilbird

(Steatornis caripensis)

Oilbirds are assigned their own taxonomic family. Oilbirds live mostly in South America and subsist almost entirely on high-fat fruits like palm fruits, which they eat while flying around at night. Oilbirds fly through the dark during the day, too, nesting and roosting deep in caves that they navigate with echolocation. -

Limpkin by Chris Payne via Birdshare. Limpkin

(Aramus guarauna)

Limpkins have a very unusual diet among birds, subsisting almost entirely on snails. The Limpkin’s bill is uniquely adapted to snail foraging. When closed, its bill has a gap just before the tip that makes the bill act like tweezers. The tip itself is often curved slightly so it can be slipped through the chamber of the snail. -

Upland Sandpiper by Charmaine Anderson/Macaulay Library. Upland Sandpiper

(Bartramia longicauda)

Upland Sandpipers are accorded their own genus, and have the relatively unusual habit within sandpipers of living, at all times of the year, in tall grass. Their impressive long-distance migration takes them from the Great Plains of North America to the pampas and grasslands of the high Andes of South America. -

Pied-billed Grebe by Etienne Artigau/Macaulay Library. Pied-billed Grebe

(Podilymbus podiceps)

Many of the world’s oldest extant bird lineages are associated with water, and grebes are no exception. The Pied-billed Grebe is the last living member of its genus, and thus unique among grebes. They are so acutely adapted to an aquatic existence that they are virtually unable to walk on land, so they build a nest atop a mat of floating vegetation. -

Elf Owl

(Micrathene whitneyi)

Elf Owls have always been a bit of a taxonomic mystery, and are assigned to their own genus. They are the lightest owls in the world, with the unique habit of frequently using woodpecker cavities in saguaro cacti for nesting. -

Osprey by David Brown/Macaulay Library. Osprey

(Pandion haliaetus)

Taxonomically, Ospreys are assigned to their own family, and they live on every continent except Antarctica. Ospreys have been successfully subsisting on a diet of fish for an estimated 50 million years. Having originated so long ago, it’s very likely that they occurred on Antarctica, too, when the continent was warmer.

-

Eliot Miller is an Edward W. Rose postdoctoral fellow at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library