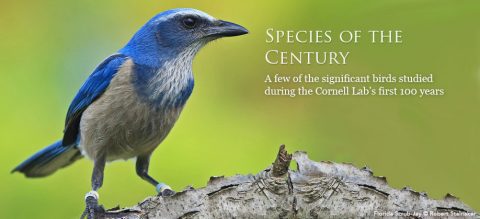

A Century of Bird Study

January 15, 2015

From its earliest days in a drafty attic in Cornell’s McGraw Hall, the Lab of Ornithology has pioneered new research methods and technologies—and engaged bird watchers in gathering scientific data.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology was founded 100 years ago. Just think about that. In the year 1915, the United States was still two years away from entering World War I; the most advanced aircraft were primitive biplanes made of wood and canvas; movies were silent, and would be for about a dozen years longer; the first radio station in America had yet to be founded; and commercial television was still more than three decades in the future. But the world was on the cusp of a new era in which some of the most significant technological advances in the history of humankind would unfold. The Cornell Lab was there to take advantage of these breakthroughs and, in many cases, help shape them.

The story of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology begins with its visionary founder, Arthur Augustus Allen. You can easily draw a straight line from his work here in the early to mid 20th century to everything that came after. He laid the groundwork for so many things that are now part of the culture of the Lab, virtually embedded in its DNA—a can-do attitude (if a piece of equipment or a research technique doesn’t exist, Lab scientists invent it); a strong interest in ecology and conservation; and an abiding belief that bird watchers can gather important scientific data.

Arthur Allen’s connection with Cornell University began early—he came here as an undergraduate in 1904, at the age of 18, and earned a bachelor’s degree in 1907, a master’s degree in 1908, and a Ph.D. in zoology in 1911. Allen’s dissertation—an ecological study of the Red-winged Blackbird—was written decades before ecology became a major field of biological study. In the introduction to his thesis, he wrote: “Where can [someone] find set forth the factors which determine that one bird shall inhabit the open fields, another the undergrowth, and a third the marshes? What are the adaptations of each species to its peculiar habitat, and how has each become dependent on it?” He sought to remedy that lack of information on the Red-winged Blackbird and its cattail marsh habitat. Thanks to Allen, studying ecosystems and the bird populations that depend on them has been a major part of the Cornell Lab’s research since its founding.

Allen had boundless energy and enthusiasm. After receiving his Ph.D., he led an expedition to South America, sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History, and discovered 15 species of birds previously unknown to science. When he returned to Cornell, he was appointed professor of ornithology. A dedicated conservationist, Allen also taught the country’s first wildlife conservation course in 1919 at Cornell and later served as the second president of The Wildlife Society.

In the 1920s, Allen turned his research efforts to the Ruffed Grouse. He shot motion-picture footage of the grouse and used it to determine how the birds make their courtship drumming sound. (In a recent echo of his work, Cornell researcher Kim Bostwick used high-speed video to find out how Club-winged Manakins make their distinctive courtship sounds.) And Allen was the first person to breed the Ruffed Grouse in captivity, another theme that would continue at the Lab. Years later, in the early 1970s, Tom Cade—a Cornell professor and director of raptor research at the Lab—launched a captive-breeding project with the critically endangered Peregrine Falcon, raising more than 5,000 young peregrines to return to the wild after the species had been nearly driven to extinction by DDT. (The Peregrine Fund, which Cade founded, was spawned at the Lab, as was the International Crane Foundation, which was launched in the 1970s by George Archibald, who had bred cranes in captivity at the Cornell Lab as a grad student.)

From the time of Allen’s appointment as a professor of ornithology in 1915 to the 1940s, Cornell was one of the few institution in America offering graduate studies in ornithology. Many leaders in the field conducted their early research at the Lab and went on to found graduate programs in ornithology at other universities. Notable grad students of Allen’s were Olin Sewall Pettingill and Peter Paul Kellogg, both of whom went on to become directors of the Lab; famed bird artist George Miksch Sutton; legendary field ornithologist Ludlow Griscom; and many others.

In addition to inspiring a generation of professional ornithologists, Allen was a great popularizer of bird study, encouraging ordinary people to learn more about birds and gather scientific data on them. He was outgoing and friendly and, above all, approachable. He presented numerous lectures across the country (illustrated with photographs and films he had taken himself ), led local bird walks constantly, wrote countless articles for popular magazines (such as National Geographic), made record albums featuring bird songs, and produced a weekly radio show. He firmly believed that increasing public interest in birds was the most effective way to promote bird conservation.

He was also a pioneer in wildlife photography—shooting both still photos and motion pictures of many species—and natural sound recording (see below). In 1929, he became the first person ever to record the songs of wild birds. These technologies are still an important part of the Lab’s work. The Library of Natural Sounds that Allen and co-researcher Peter Paul Kellogg launched in the 1930s has evolved into the Macaulay Library, the world’s largest collection of wildlife sound recordings. And in the 1980s, another sound-research unit, the Bioacoustics Research Program, was launched to develop and deploy new methods of tracking, counting, and monitoring a wide array of wildlife species. The Lab’s Multimedia department sends teams of cinematographers and sound recordists around the world to document vanishing species, such as Spoon-billed Sandpiper, Gunnison Sage-Grouse, and Philippine Eagle, much as Allen did with the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in 1935.

In addition to these, we now have programs in Bird Population Studies, Conservation Science, Citizen Science, Evolutionary Biology (with a full DNA lab), Information Science, and Education. There just is not enough room in the space of a magazine feature article to do justice to all the many initiatives and research efforts the Lab has engaged in during its remarkable first century. I look around me at the Lab. I speak to dedicated researchers working in so many places around the world—studying not just birds but also marine mammals, forest elephants, and more—and I can only imagine how great this would make Arthur Allen feel, watching the fruit of the seeds he planted a century ago flourishing at Sapsucker Woods.

The Birth of Natural Sound Recording

One of the most enduring legacies of the Cornell Lab’s early days is surely its pioneering efforts in the study of wildlife sounds. The field of “biological acoustics” was virtually invented here in the late 1920s, just a couple of years after the 1927 Al Jolson film, The Jazz Singer, amazed audiences around the world with its synchronized sound, signaling the birth of talking movies.

Arthur Allen quickly realized what a boon sound recordings of birds would be to ornithology students. In his classes, he had already been emphasizing the importance of knowing bird songs and calls to be able to identify species, but unfortunately no recordings of bird songs existed. Then, by a stroke of luck, the Fox-Case Movietone Corporation came to Allen for help in recording bird songs. Allen took them to nearby Renwick Park (now called Stewart Park) at the southern end of Cayuga Lake in Ithaca.

At first the technicians from Fox-Case were unable to make any recordings. They would approach the birds with their massive equipment and scare them away. Then Allen took over and set up a remote microphone beside a known singing perch of a Song Sparrow, where he knew the birds would return and sing, and he was able to make a recording. On that historic day, he recorded Song Sparrow, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, and House Wren—the first recordings ever made of birds in the wild.

Of course, the Movietone recording system left much to be desired. Bulky, difficult to use, and primitive, it would convert sound vibrations into electrical impulses and then into light of varying intensity, which was then captured on motion-picture film. After developing the film, the process was reversed, converting the light images back into electrical impulses, which were then changed back into sound.

But Allen was fortunate enough to have an eager team working with him in this sound-recording endeavor. His grad student Peter Paul Kellogg, who had begun teaching ornithology classes at Cornell in 1929, jumped right in and started addressing the many challenges of this new technology.

“We now understood the principal problems in recording and the shortcomings of the equipment,” Kellogg wrote. “We understood, too, that if we were to achieve any kind of perfection, we would have to develop our own specialized equipment and techniques for field work.” (This emphasis on developing new technologies has long been a hallmark of the Lab.)

They were joined by Albert Brand, a former stockbroker who had left his financial career in 1928 and come to Cornell as a special student. He funded much of their early sound work, buying equipment and financing expeditions. He also produced the first record album of bird songs.

Another important figure at this time was Peter Keane—a Cornell undergraduate who spent most of his spare time at the Lab. (Keane passed away recently, in early 2014, at the age of 103.) He came up with the concept of using a huge acoustic dish called a parabola to record birds, making it possible to isolate the sound of an individual singing bird. The team made their first parabolas themselves, casting them and shaping them by hand. The parabola has been a universal tool of wildlife sound recording ever since.

Kellogg went on to develop the design concept for the first portable tape recorder during his sabbatical leave in 1949–50. The recorder, manufactured by the Amplifier Corporation of America in 1951, weighed less than 20 pounds and revolutionized the recording of wildlife sounds in the field.

A remarkable amount of groundbreaking work was accomplished in those early years. Although the Lab’s sound collection only had recordings of 31 bird species by the end of 1931, it was already the largest birdsong collection in the world. But that was only the beginning. The Lab’s Macaulay Library now has tens of thousands of archived sounds from a wide range of wildlife species, including birds, bats, whales, elephants, frogs, toads, fish, insects, and more.

The pace of innovation in sound studies at the Lab has never slowed. The Lab’s Bioacoustics Research Program is a hotbed of activity, constantly designing new technologies and equipment to monitor the wildlife of the world: remote recording devices to detect forest elephants in Africa, whales and other sea life in the oceans, migrating birds flying high overhead at night, and so much more. The group has even developed and deployed a sound-detection system in Massachusetts Bay that identifies rare North Atlantic right whales present in the bay and warns ships to slow down and avoid colliding with them.

It’s amazing to think that all of this began 100 years ago with Doc Allen and a handful of students at the Cornell Lab.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library